On the mountains, furious battles took place; a life of hell among avalanches and frostbite. Men found themselves fighting against the mountain first, and then against each other.

A front that was totally unknown to Italian soldiers. Austrians, retreated into a dominant position on the crests, in a defence position, were kept under pressure by continuous Italian attacks.

Whenever positions could not be gained with assaults, attempts were made to blow them up with mines.

General Winter made more victims than cannons.

A front where technology entered in an arrogant manner: new roads were built, audacious paths were opened, railways, cableways, phone and electricity grids were created.

The face of the Dolomites would never be the same again.

“Making war is one thing; killing a man is something else”.

E. Lussu, Un anno sull’Altopiano, published by Mondadori

In 1872, Major Captain Giuseppe Perrucchetti came up with a defence model for Alpine borders and suggested innovations for the military posts in border areas. The local male population would be recruited in border areas, so as to have as many defence units as there were Alpine passes to be protected.

According to Perrucchetti, soldiers destined to these units needed to be used to the harsh climate, to the fatigue of moving around in the mountain, to the rough, dangerous terrain and to the discomfort of weather conditions. Officers were required to have a deep and direct knowledge of the territory, Alpines first and military second.

This is how, on 15 October 1872, the first embryo of the Royal Army’s mountain troops was devised.

Eight regiments fought in the war, usually consisting of about ten battalions each.

Infantry was, in all armies, considered the skeleton of the Armed Forces, to the point it was given the name the Queen of Battles. Infantry has roots in the legions of ancient Rome, but the official date of its birth is associated to the creation of the Italian army, on 4 May 1861.

Its use relied on the possibility to attack en masse, and its goal was basically that of resisting and defending the entire front, when it was not used in assaults. During WWI, most peasants recruited as soldiers ended up in the infantry. These were usually men of little formal education and picked directly from mobilisation lists. No particular specialisation was necessary; a few months of training were sufficient to have them occupy a trench, from the seashore to the mountains.

126 Brigades operated during the war, each consisting of two regiments.

The Corpo dei Bersaglieri was created with a Royal commission on 18 June 1836 by Charles Albert of Sardinia, after a suggestion of the then captain Alessandro La Marmora.

The duty assigned to these new specialised troops included the typical functions of light infantry - exploration, first contact with the enemy and flank support to the line infantry - but it was characterised, as intended by their founder, by an unheard-of speed of execution of their jobs and by a versatility of use that turned their members into an agile militia, always ready to intervene quickly wherever they were needed.

21 Bersaglieri regiments operated in the Great War, usually consisting of three battalions and one bicycle troop each.

The Tyrol “tiratore al bersaglio” (target shooters) had a very long tradition, dated to the 14th century, of defenders of the country.

The first systematic organisation was in Landlibell, on 23 June 1511: according to the severity of the danger, each judiciary area had to supply a certain number of armed men for the defence of Tyrol.

With the regulation of 25 May 1913, the Schützen were militarised and aggregated to the Landsturm.

When Emperor Franz Joseph ordered the general mobilisation on 18 May 1915, able soldiers were already in the Eastern front. The Standschützen that were to defend the border were very young (from 16 to 21 years old), old (above 42), or retired and unable to perform normal military service, all voluntary.

They were assured they would have remained in the second line, in positions protected by concrete walls; they were sent instead exactly to the most exposed and tactically important points of the high-altitude front, where they defended their own land with valour. There were about 23,000 recruited men.

The troop democratically chose its own officers.

The Tyrol Standschützen were recognisable by the green fabric insignia with a red Tyrol eagle.

They were organised into several companies and battalions spread all over the South and North Tyrol territory.

The Standschützen were the undying symbol of the strenuous defence of the Tyrol front line, as they were directly involved in the defence of their own families and property during the war.

Their tradition continuous with glory in the current Schützen companies.

The Landesschützen, “local fusiliers”, was a light infantry corps of the Austrian-Hungarian army, either recruited or voluntary, belonging to the mountain troops of the Landwehr, the national Austrian army that was part of the Austrian-Hungarian armed forces until 1918. The Landesschützen were recruited exclusively in Tyrol, and they spoke either German (North Tyrol - South Tyrol) or Italian (Welschtirol), and, together with the Gebirgsschützen (“mountain fusiliers”, mountain troops recruited in Styria, Carinthia and High Austria), made up the Alpine troops.

In the previous years of peace, the Landesschützen had been allied with the Kingdom of Italy all along the border, from the Stelvio Pass to the Carnic Alps.

In 1917 they were re-christened as Kaiserschützen (literally “imperial fusiliers”) for war merits. In times of war, each regiment was expected to double its soldiers of the service battalions, enrolling trained reserve soldiers up to 42 years old, forming also two other battalions: a Marschbataillon (marching battalion) and a battalion for complementation and training (Kader-Ersatzbataillon) that would take the regiment to up to 4 battalions of 1,000 men each plus services, for a total of 4,000 men.

They were recognisable from the forward-pointing cockerel feather on their fighting and parade berets, their hunting horn with a Tyrol eagle in the centre, the Imperial monogram FJI or K on officers’ combat hat, sports style jacket with gusseted pockets and slit on the back, green shoulder piece with silver stitching around the edges, with the Imperial monogram embroidered for the officers, edelweiss on green insignia on the jacket collar, and short rifle and mountain equipment.

First Landesschützen Regiment

“k.k. I Landesschützenregiment Trient” (assembled on 1 May 1893)

had its headquarters in Trento, and its battalions were organised as follows:

I. in Trento

II. in Strigno

III. in Ala and (after 1913)

IV. in Rovereto.

Summer training took place in small barracks or at hotels rented for this purpose in Strigno, Brentonico, Folgaria, Lavarone, Luserna and Pieve Tesino.

Its operational sector covered the Alps from the border with Switzerland to the Tonale Pass.

Second Landesschützen Regiment

“k.k. II Landesschützenregiment Bozen” (assembled 1 May 1893)

had its headquarters in Bolzano and its battalions were organised as follows:

I. in Merano

II. in Bolzano

III. in Riva del Garda.

The summer training took place in Daone, Storo, Pinzolo, Riva del Garda, Pejo and Vermiglio.

Its sector of use in the event of war ran from the Tonale Pass to Riva del Garda.

Third Landesschützen Regiment

“k.k III Landesschützenregiment Innichen” (assembled on 1 March 1909)

was stationed at San Candido-Innichen in the winter. In the summer it spread, in addition to these two villages, over Predazzo, Passo Rolle, Moena, Passo San Pellegrino, Penia in Val di Fassa, Sexten.

Its battalions were organised as follows:

I. in Fiera di Primiero

II. in Predazzo

III. in Cortina,

IV. (after 1913) in Innichen.

The regiment’s command was located in San Candido-Innichen.

Its operational sector covered from the Dolomites of the Cadore with the border with Carnia.

The Kaiserjäger or K.u.k. Kaiserjäger (Imperial Hunters) were a light infantry division of the Austrian-Hungarian Imperial Army, recruited from the Alpine territories of the Empire, in particular from the county of Tyrol, which included the territories of current Austrian northern and western Tyrol, Alto Adige (Südtirol/South Tyrol), Trentino (Welschtirol or southern Tyrol).

Their denomination, which set them apart from the common Jäger divisions, came from the particular loyalty, always displayed by the Tyrol population towards the Emperor. They were considered, in a state that had never had a fighting royal guard, a division in charge of protecting the country’s sovereign.

The Kaiserjäger were not an elite division specialised in mountain warfare, and, apart from their name, their training, weapons and uniforms did not differed from those of common hunter divisions.

Their division can be compared with Italian Bersaglieri.

However, they consisted mostly of troops recruited from Alpine areas, and were therefore perfectly adapted to war in the Dolomites front.

They stood out for their unfailing battle tenacity. Their fame has lasted to this very day.

They bore green insignias on the lapel; officers had the symbol of the hunting horn with a Tyrol eagle in the centre on their hats (eagle with a single had turned to the right).

First regiment

Nationalities: 58% Germans - 38% Trentino - 4% others

Command/I./II. Battalion in Trento (Trient)

III. Battalion at Levico (Löweneck)

IV. Battalion at Innsbruck

Second regiment

Nationalities: 55 % Germans - 41% Trentino - 4% others

Command/I./II. Battalion at Bolzano (Bozen)

III: Battalion at Merano (Meran)

IV. Battalion at Bressanone (Brixen)

Third regiment

Nationalities: 59% Germans - 38% Trentino - 3% others

Command/II./ III. Battalion at Rovereto (Rofreit)

I. Battalion at Riva del Garda (Reif am Gardasee)

IV. Battalion in Trento (Trient)

Fourth regiment

Military target practice of the III. Regiment Tiroler Kaiserjäger at Rovereto (April 1902)

Nationalities: 59% Germans - 38% Trentino - 3% others

Command/III. Battalion in Trento (Trient)

I. Battaglion at Mezzolombardo (Welschmetz)

II. Battalion at Mezzocorona (Kronmetz)

IV. Battalion at Hall in Tyrol

Marshall’s hat of the 7th Alpine Regiment, with grey-green silk war badges.

Beret model 1909 of Colonel commander of the 23rd infantry regiment of the Como Brigade, operating with the Ferrari division in the Lagorai area. Grey-green silk war stripes.

Enlisted rank’s berets, 91st infantry regiment of the Basilicata Brigade, which operated in the Cima Bocche area.

Bordeaux fez of the 1st Bosnian infantry regiment.

In 1914, when the work began, enemy armies got to the battlefield without any head protection. It was not until the first half of 1915 that the first helmets were adopted.

The display shows 2 metal helmets, model 1915, made in France but destined to be used in Italy (they were named Adrian, after their designer), of two different versions. Observe their inner sides and note how the leather is cut differently - in the case of the first model, it comes from a single piece.

Next to them sits a 1916 model made in Italy, with cap and brim moulded in a single piece.

To defend the entire South Tyrol, about 30,000 local men were mobilised, militarising a sort of previous association of snipers called Standschützen, as they had voluntarily enrolled into a shooting range. The men who were to defend the border were very young (from 16 to 21 years old), old (above 42), or retired and unable to perform normal military service.

Only some of the officers of the Imperial Army understood how important this corps would be, from the moment they had grouped in the squares of Alpine villages to defend their borders. To the eyes of most officers, however, it seemed absurd to give any value to this group of scruffy, poorly-trained soldiers.

In spite of this, these men became, to the eyes of the Press Office of the Austrian Army’s Supreme Command, a source of patriotic inspiration, the symbol and the emblem of a strong participation that was deeply felt: the Tyrol soul, which, just as in the time of Andreas Hofer, arose to fight back the aggressor.

War artists were therefore put to work immediately, to portrait and emphasise these aspects.

In the history of the Great War, the Standschützen saga is a unique case, not only because no other peoples have reacted in such a unitary and brave manner to an enemy’s attack, but also because Tyrol inhabitants resisted with unsuitable weapons, enrolled even when their age was not adequate to the strains of high mountain war, remaining firm in their own fighting positions exactly because their families were so close.

In Moena, the first Shooting Range was built in 1858, proving that even back then there was, in the village, a society of non-enrolled shooters, i.e. a company of Standschützen, or “Stonc” in Ladin. Supported by the military administration of Tyrol, in particular the Landesschützen, they incarnated an ancient self-defence tradition of local populations and simultaneously perpetuated the well-rooted and diffuse tradition of target shooting.

However, it was only in 1887 that the law officially acknowledged the military role of the Standschützen as part of the Landsturm, the territorial militia, as last reserve.

Unfortunately the enrolment books of the Moena Standschützen were not preserved, but their active presence in the town can be proven, albeit indirectly, by the building of three different Shooting Ranges, the last of which is on the right margin of the Avisio, with the shooting outlines located here in Navalge. There is also documentation proving that in 1892 the Standschützen Company of Moena had their flag blessed. Sadly, no description of the flag remains.

In the summer of 1914, Tyrol authorities began to prepare a detailed military plan to defend the border with the Kingdom of Italy, which included the use of the Standschützen with logistic and surveillance duties. This mobilisation program added the Moena Company to the Cavalese battalion, according to a traditional allocation that dated as far back as the Landlibell (1511). In December 1914, for instance, those enrolled in the Shooting Ranges of Moena and Forno were made to form a company of 3 platoons, for a total of 128 Schützen and 71 bearers.

In the spring of 1915, many Moena locals, very young or very old men, or not yet enrolled, enrolled themselves in the local Shooting Range. As Standschützen, they were used in the town for fortification works, therefore under the Bauleitung, the Austrian-Hungarian Military Engineering. They were paid for their work and were fed as well. The Bauleitung was commanded by First Lieutenant Richard Löwy, remembered as a great benefactor of the town, as can be read in the plate in the garden next to the street named after him. The general belief during those months, from the commander to the last of the Standschützen, was that enrolling oneself at the Moena Shooting Range would ensure their remaining in the town with their own families. This idea was also supported by certain Tyrol propaganda. This is why in the spring of 1915 the number of Moena Standschützen had gradually increased, in spite of the repeated new recruitments to regular formations, amounting to about 170 men.

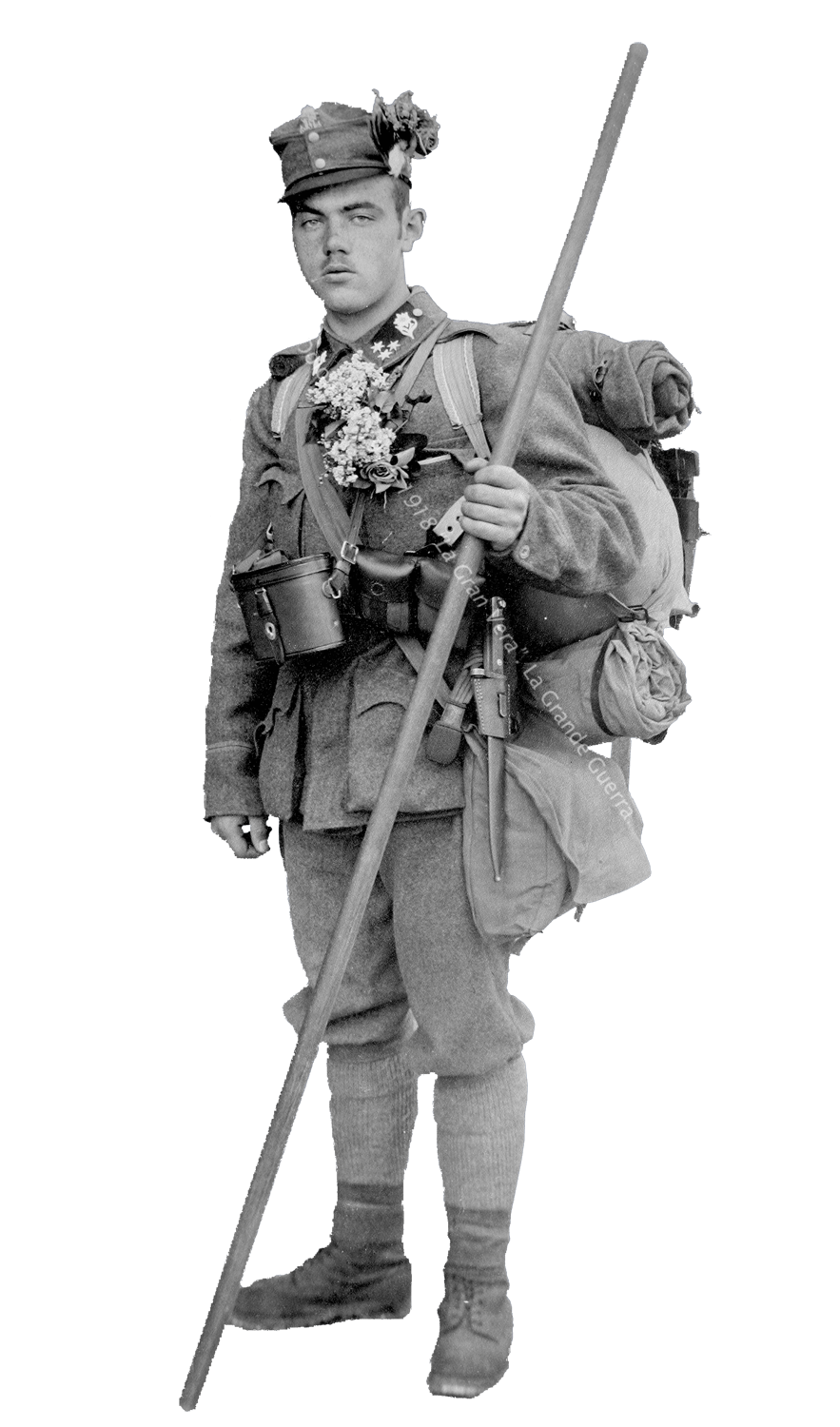

In May 1915, when all Tyrol Standschützen were mobilised, the Moena Company was considered an autonomous formation, subject to the command of the garrison in the Moena fort - i.e. First Lieutenant Löwy. The Standschützen were armed in part with old Werndl rifles and in part with more modern Mannlicher. Field uniforms, on the other hand, were not sufficient for all men, to the point that some were forced to wear, at least early in the war, the traditional tobacco-coloured jacket with a yellow and black band around the arm.

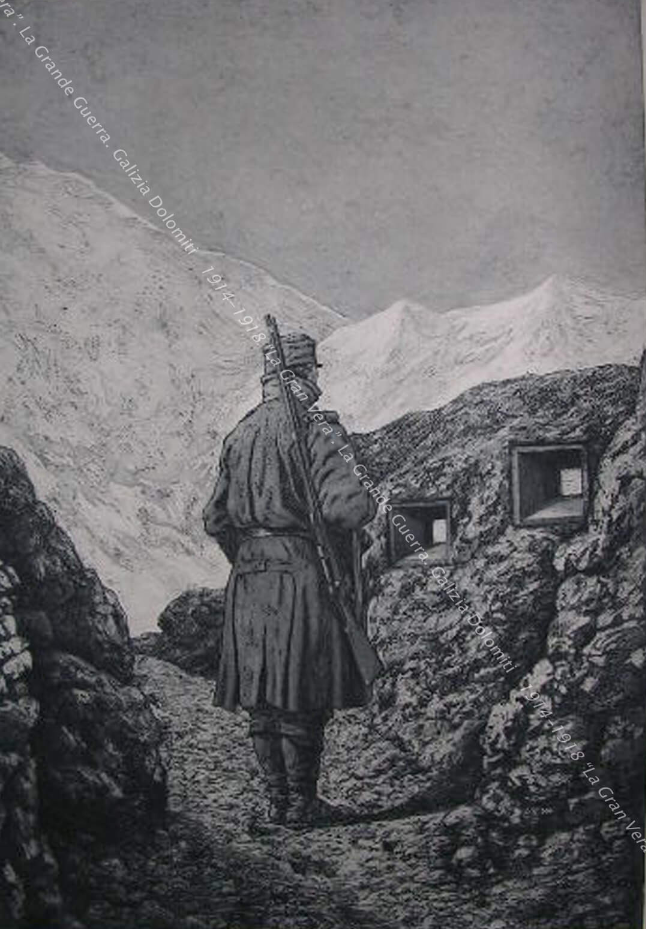

A Standschützen scrutinises the San Pellegrino Valley from the Austrian trench of Passo delle Selle. The low concrete wall is still visible to the right of the Passo Selle Shelter, right after taking Alta Via Bruno Federspiel. In the background, Cima Allochet, taken for a few hours by the Bersaglieri of the 3rd Regiment during the Italian assault of 18 June 1915.

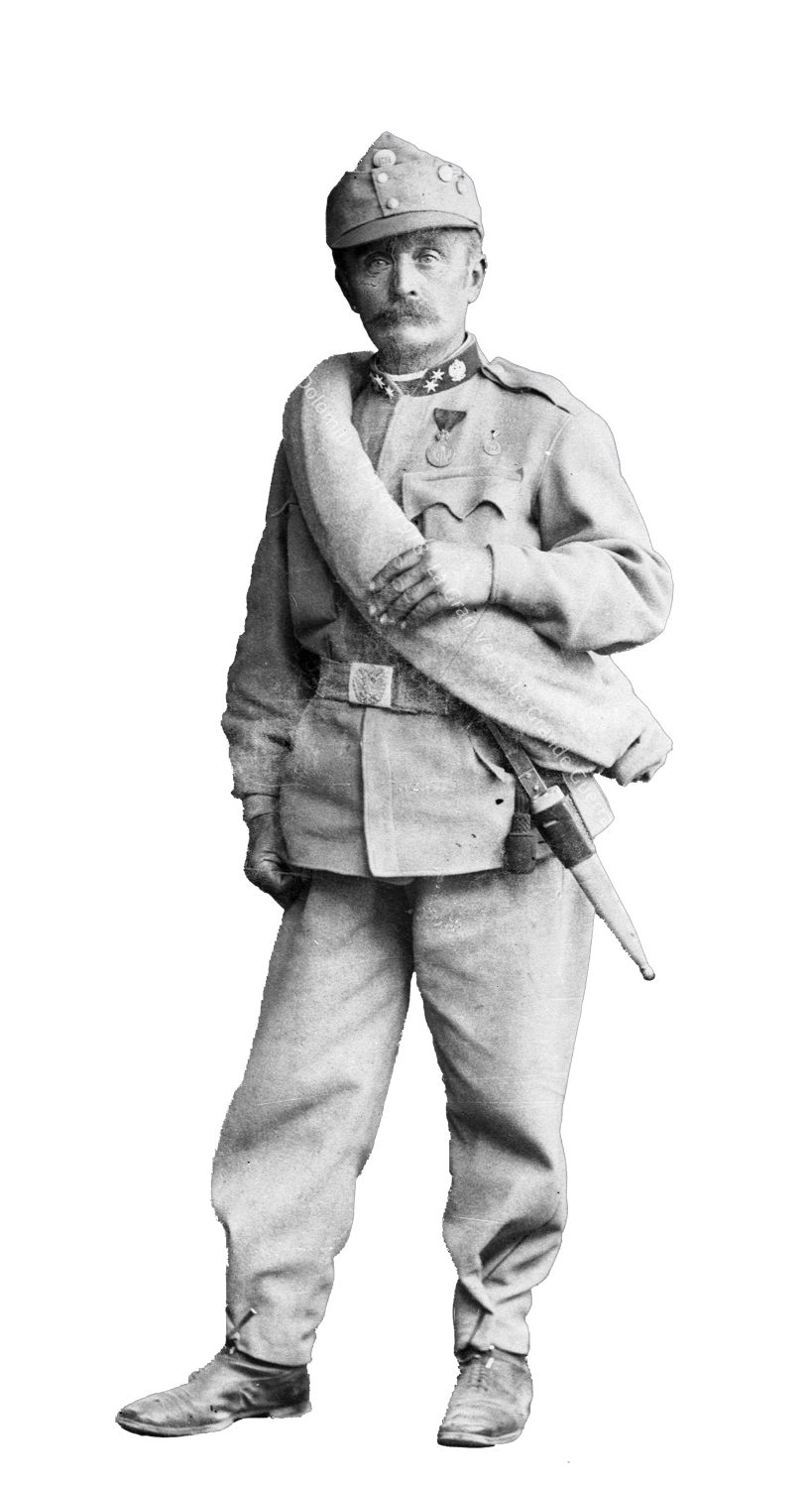

Group of elderly Standschützen of the Moena Company.

According to the ancient tradition of the Standschützen, the company itself elected its commanders: Captain Federico Felicetti Tomajela, born in 1867, forester and peasant, Lieutenant Vigilio Pettena Mutol, born in 1864, construction entrepreneur, and Giuseppe Dellantonio, born in 1869, builder, Quartermaster Valentino Pezzè, school teacher.

The Moena Standschützen remained in the town with various duties, including sentry and livelihood services in the front that was being consolidated in the summer of 1915, from the Lusia Pass to Le Selle and Costabella, including Cima Bocche. This was the norm until October 1917, when the Standschützen Company of Moena still had 157 men and 1 officer.

In November 1917, after the Italian army retreated from the heights above Moena and from the rest of the Dolomites front, the Company of local Standschützen was transferred to Low Trentino (Riva, Nago, Villa Lagarina) and then again, in the summer of 1918, to Vigo Cavedine, where they were used to collect firewood. In that situation, the Moena Company and those of Campitello and Pozza were added to the Standschützen-Gruppe Fassatal.

Finally, in October 1918 the Moena Company returned to the valley, to be used to collect firewood in Paneveggio and surrounding areas, where it was dissolved when the war ended.

The autonomous company Standschützen Moena, consisting of 171 men, was created under the supervision of Lieutenant Richard Löwy (made honorary citizen of Moena on 10 September 1916 and died in Auschwitz in 1944). It was later made part of the Cavalese Battalion, commanded by superior offices Covin and Hafner, and depended on the 179th Imperial Royal Infantry Brigade.

The company that enrolled Moena citizens, destined mainly to support services for the troops in the very first line, worked in the front of Cima Bocche and, after October 1917, in the Ponale area, near Riva del Garda. It returned to its original town after the armistice of 4 November 1918.

At 17 years of age, Giuseppe Felicetti was employed in the transportation of water to the machine guns of the observatory and to the other very first line positions, an incredibly dangerous job. Another duty was burying the dead. He was also sent to Moena for private errands for higher officers. He kept a war diary that was sadly left in the mountain stations while pursuing the Italians due to the Caporetto route.

During the summer, we would spend hours on the bench in front of his house in Someda, talking about his experience as a soldier.

Great humanity and strong emotions thinking of the horrors of war and all the men who fell from both sides. The vision of the lines of Italian soldiers mowed by machine guns during the July 1916 assault at the Observatory, the mountains of Italian dead in the Kraiz (Death Gully) beneath the observatory, the extreme pity felt while hearing the screaming of the wounded left to themselves beneath the barbed wire.

His friend Arcangel Caiosta, who was afraid of nothing, would stick his head out of the trench to watch the assaults. He was very proud of never having killed anyone. He also remembered his visits to his mother when he would walk down to the town to find anything, even just an extra egg; the continuous hunger, the avidity with which he would eat the “tubes” (the word he used for the maccheroni pasta provided to the troops by Pastificio Felicetti, the pasta factory founded in 1908 in Predazzo by Valentino Felicetti, a high-quality production which helped feed soldiers and locals over time).

When, in the 1980’s, he heard of my wish to create a war museum in Val di Fassa, so as not to lose the memory of those who had fought for the Hapsburg Monarchy, he gave me the coat and the hat he wore during the last year of the war.

Today these relics are part of the collection of the Ladin Museum of Fassa.

Michele Simonetti

“Federspiel”

Yellow-black band (the Hapsburg colours) used by the Standschütze volunteers after 24 May 1915, before the official uniforms were distributed.

Postcard of the 179th Imperial Royal Austrian Infantry Brigade.

Glimpses of Moena, Lusia, Ceremana and Predazzo by Albert Reich, published in the book “Dolomiten Wacht”.

The ancient emblem of the Fassa Valley, the shepherd, was used to make a brooch sold to raise funds for war orphans and widows, like the Vivant bands.

Cardboard soldiers Moena boys used as toys.

Aerial photographs taken in 1917 by Italian aviation, identifying Austrian artillery around the town.

Stamps issued by the Commune of Moena to purchase rationed food products.

Moena Gendarmerie in 1914.

CHENETTI GIUSEPPE late Pellegrino batol, 14.6.1888 - 27.6.1916

CHIOCCHETTI BATTISTA late Battista giacomac, 11.8.1888 - 14.9.1914

CHIOCCHETTI BATTISTA late Volfango boracanela, 1888 - 1914

CHIOCCHETTI BATTISTA late Giuseppe ragnol, 23.3.1891 - 4.10.1915

CHIOCCHETTI BERNARDO late Simone bernard, 1879 - ott.1914

CHIOCCHETTI BERNARDO late Battista ragnol, 2.11.1890 - 28.8.1914

CHIOCCHETTI BORTOLO late Giacomo gianot, 8.9.1889 - 6.7.1915

CHIOCCHETTI GIOVANNI late Battista pelin, 1889 - 8.10.1920

CHIOCCHETTI GIUSEPPE late Nicolò marìo, 1871 - mag. 1918

CHIOCCHETTI GIUSEPPE late Battista chitoto, 19.1.1878 - 6.3.1915

CHIOCCHETTI GIUSEPPE late Volfango borcanela, 21.5.1892 – 28.8.1914

CHIOCCHETTI GIUSEPPE late Battista ragnol, 28.9.1893 - 24.7.1916

CHIOCCHETTI LUIGI late Andrea tentor, 30.5.1877 - ott. 1918

CHIOCCHETTI SIMONE late Valentino steto, 1884 - ott. 1914

CHIOCCHETTI SIMONE late Domenico moro, 1886 - ag. 1916

COSTA FELICE late Pietro, 1881 - 11.2.1919

CROCE BATTISTA late Domenico pel, 14.11.1876 - 13.8.1918

CROCE FELICE late Bortolo fantonel, 2.8.1892 – 28.8.1914

CROCE VALERIO late Antonio schmit, 1868 - apr. 1917

DAMOLIN GIACOMO late Giacomo stainer, 27.4.1883 – 1.11.1914

DAPRA’ SIMONE of Giacomo cialin, 23.10.1890 - 21.9.1914

DEFRANCESCO DOMENICO late Giacomo giuselon, 25.9.1897 - 21.6.1916

DEFRANCESCO SIMONE late Giuseppe marea, 14.9.1884 - 7.12.1917

DELEONARDO DOMENICO late Giovanni polo sorte, 1886 - mag. 1915

DELEONARDO LUIGI late Giovanni polo, 16.7.1887 - agosto 1915

DELLANTONIO CANDIDO late Vigilio simonina, 2.12.1877 - ott. 1918

DELLANTONIO CELESTE late Giuseppe borcan, 1886 – ag. 1915

DELLANTONIO DOMENICO of Antonio caran, 10.8.1888 - 28-8-1914

DELLANTONIO GIOVANNI late Simone pist, 25.10.1876 - 9.8.1916

DELLANTONIO LODOVICO of Domenico borcan, 1889 - ott. 1914

DELLANTONIO MARCO of Andrea forno, 16.10.1899 - ag. 1917

DESILVESTRO ALFONSO late Giuseppe val, 2.8.1888 - 14.10.1916

DESILVESTRO LUIGI of Andrea val, 11.10.1895 - 30.8.1915

DEVILLE TOMASO late Vigilio fregolin, 4.12.1890 - 13.5.1915

DONEI GIOVANNI of Luigi penia, 1891 - nov. 1918

DONEI VIGILIO of Luigi penia, 8.8.1896 – 1.11.1918

FACCHINI VIGILIO late Giovanni pat, 1879 - ott. 1914

FELICETTI DOMENICO late Tomaso mariot, 1886 – ag. 1915

FELICETTI GIOVANNI of Valentino, 1893 - 1914

GANZ GIOVANNI BATTISTA late Battista rossocanalin, 3.12.1873 – 2.4.1915

PEDERIVA RAFFAELE late Vigilio tapao, 22.10.1891 - 10.4.1916

PETTENA AGOSTINO of Domenico manecia, 1884 - ag. 1916

PETTENA BATTISTA of Giulia simonzon, 15.1.1894 - 21.3.1915

PETTENA BORTOLO of Domenico goti, 10.6.1889 - 2.8.1915

PEZZE’ BATTISTA late Giorgio batesta, 23.2.1896 - 2.9.1915

PEZZE’ CAMILLO of Battista paolon, 31.12.1890 - 27.3.1915

REDOLF GIUSEPPE late Battista noder, 1893 - ott. 1914

SCOPOLI BATTISTA of Margherita scopol, 24.6.1885 - ofc. 1916

SCOPOLI MARIANO of Virginio scopol, 31.12.1892 - 28.2.1918

SOMMARIVA ANTONIO of Volfango tonolerchie, 29.10.1877 – 15.12.1918

SOMMARIVA ANTONIO of Simone tonolerchie, 2.8.1885 - 13.6.1915

SOMMARIVA VOLFANGO of Simone glindo, 5.10.1899 – 8.7.1918

SOMMAVILLA ARCANGELO late Simone piaz, 28.1.1884 - 9.6.1915

SOMMAVILLA BATTISTA late Simone semio, 11.10.1886 - 28.11.1917

SOMMAVILLA GIOVANNI late Fortunato somaìla, 1884 - ott. 1914

SOMMAVILLA LODOVICO late Simone piaz, 1891 - sett. 1914

SOMMAVILLA SIMONE late Battista zaofn tibaut, 17.4.1875 - 16.11.1918

VADAGNINI BATTISTA of Giuseppe luzio, 1.5.1886 - 11.6.1915

VADAGNINI DOMENICO late Michele cesa, 13.4.1889 - 8.7.1915

WEBER GIUSEPPE late Angelo Weber, 19.11.1883 - 4.12.1917

VOLCAN BATTISTA late Valerio vaet, 10.11.1881 - 29.5.1915

ZANON BORTOLO late Giacomo bareta, 16.10.1881 - 2.9.1914

ZANON CIRILLO late Antonio bareta, 9.2.1884 - ag. 1914

ZANON ENRICO of Giacomo, 13.8.1883 – 7.9.1914

ZANONER ARCANGELO of Giovanni gabana, 6.6.1886 – 3.5.1915

ZANONER CARLO of Domenico menegon, 23.9.1889 – 21.2.1915

ZANONER GIUSEPPE late Giuseppe mezom, 1874 - 2.7.1919

DEGIAMPIETRO Agostino Giuseppe Daniele, 17.07.1898 - 29.05.1917

DEGIAMPIETRO Giorgio Tomaso Lazzaro, 29.12.1896 – ?

DEGIAMPIETRO Luigi Giorgio, 21.01.1891 - 22.10.1915

DEGIAMPIETRO Marino Andrea, 14.08.1887 - 13.06.1915

FACCHINI Giuseppe Ferdinando, 30.04.1873 - 19.10.1914

FELICETTI Eustachio Clemente, 24.11. 1883 - 03.05.1915

FELICETTI Lazzaro Felice, 18.11.1888 - 1915

FELICETTI Valentino Giacomo, 01.01. 1876 - 06.10.1918

FELICETTI Valentino Andrea, 12.03.1888 - 1917

FELICETTI Leone Vittorio (Vito), 11.04.1892 - 13.02.1918

Curated by

Maria Piccolin Sommavilla

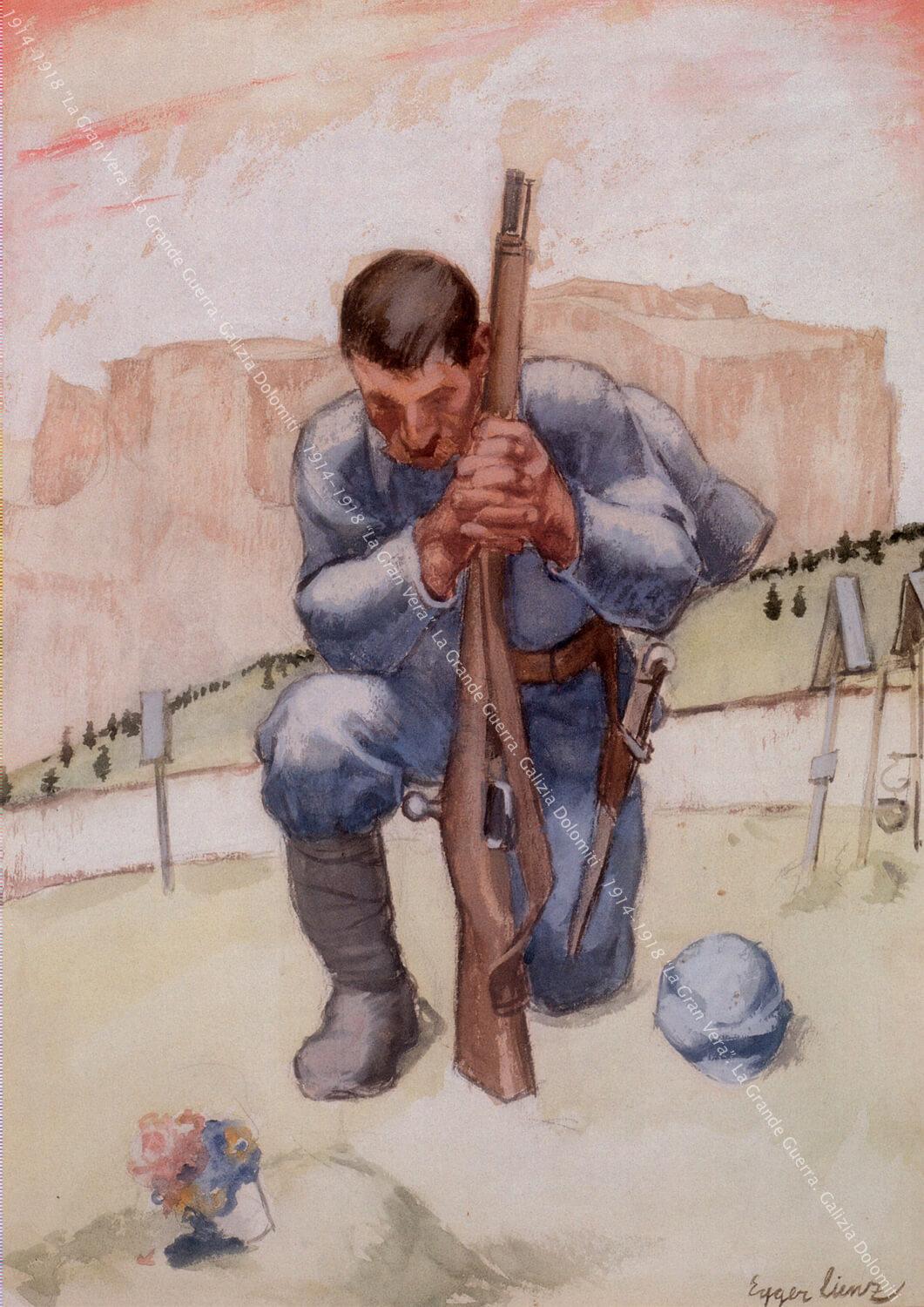

“When, three months ago, the curator of the exhibition asked me to sculpt this statue, I found is strange, because I am from the Veneto region and my great-grandparents, who fought in WWI, were Italians and fought against the Austrians.

Giuseppe Cavallin fought on Mount Cauriol and came home alive, while Giuseppe Perissinotto died of strain in the field hospital of Gemona del Friuli.

This work represents, or intends to represent, the fragility of man when faced with the pain of a dead companion of arms, or perhaps with the pain of his own conscience for having killed men like him, constrained by another flag.

Let this be a sign of peace and reconciliation.”

This is how Federica Cavallin describes her own work. The statue, in Piazza Ramon in Moena, wishes to symbolise the beginning of a historical journey to recover the memory of the Ladin people in the Great War in the Galicia and Dolomites front, later developed in the exhibition itself.

The sculpture represents an Austrian soldier in his classic fighting uniform and was placed on a Dolomite boulder, facing the front line to honour the sacrifice of Austrian and Italian soldiers alike.

It is inspired on the painting of Albin Egger-Lienz (Striebach, Lienz 1868 - Rencio, Bolzano 1926) “Der Abschied - The Departure” and on the style of Alfons Walde (Oberndorf 1891 - Kitzbühel 1958), two great 20th-century artists who were part of the war and portrayed it with great skill and modernity.

The artist took three months to sculpt the pine block, and then donated the work to the community.

This monument was made possible thanks to the contribution of the Commune of Moena and of the S.E.V.I.S. company of Moena.

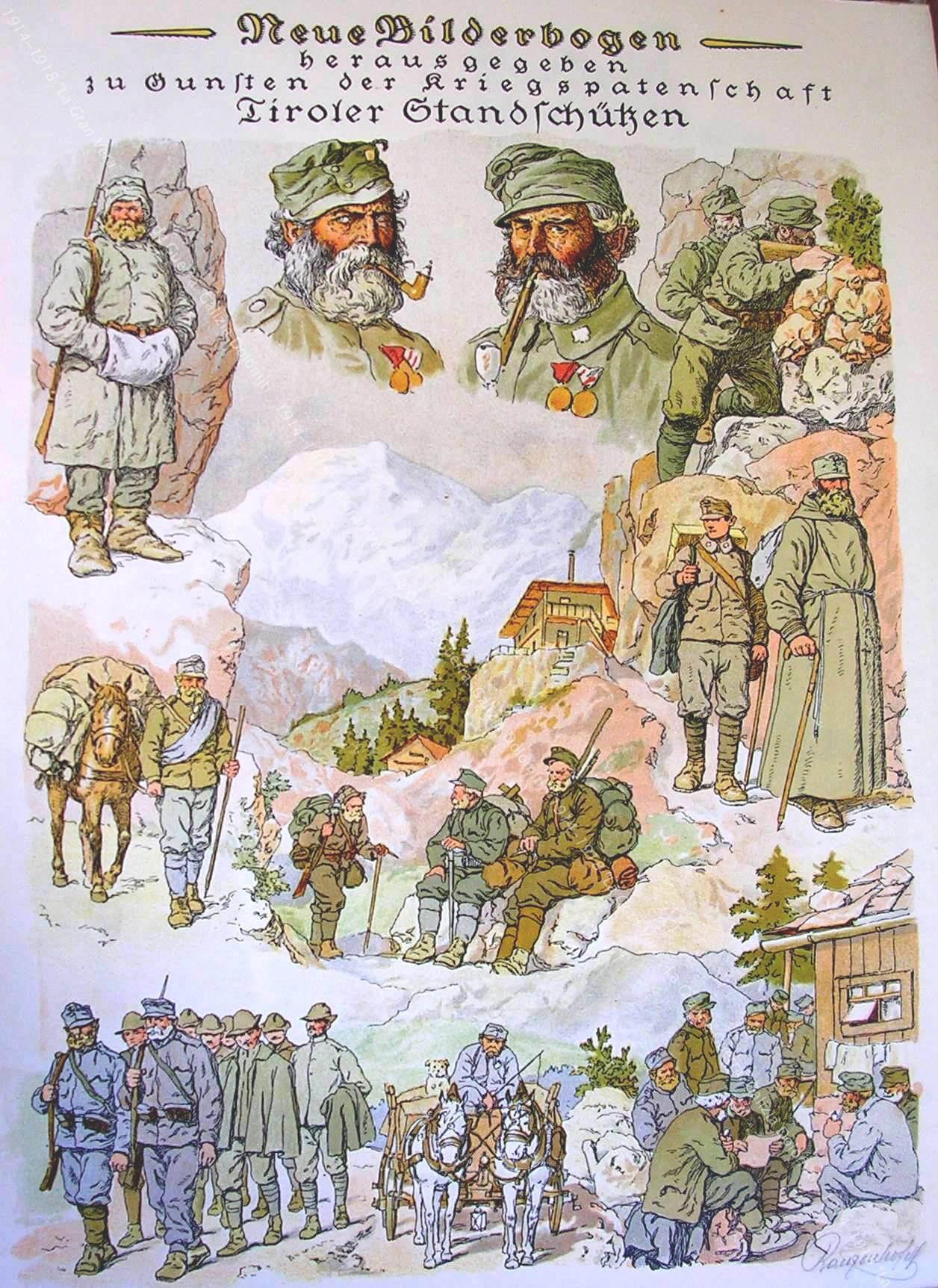

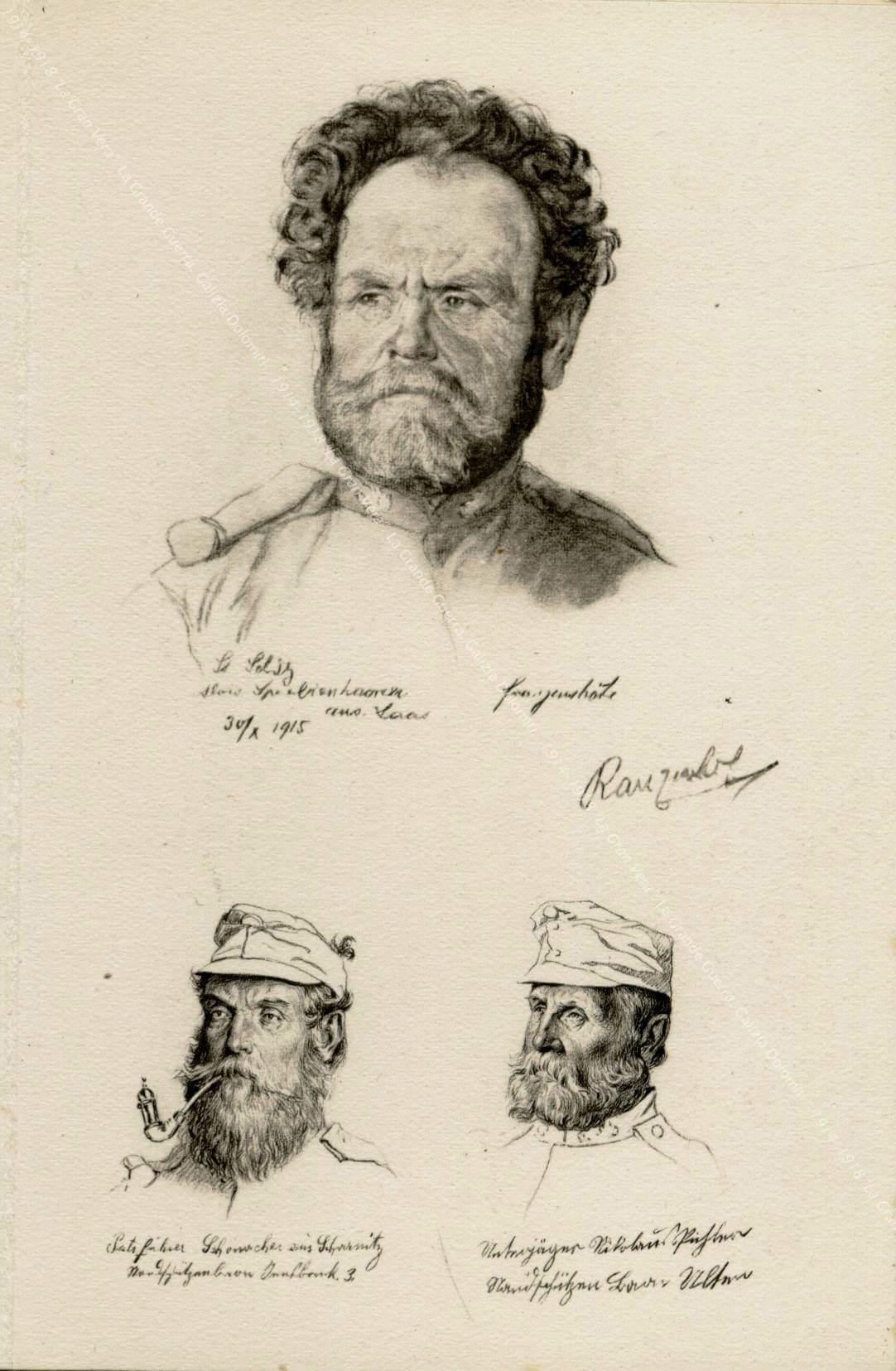

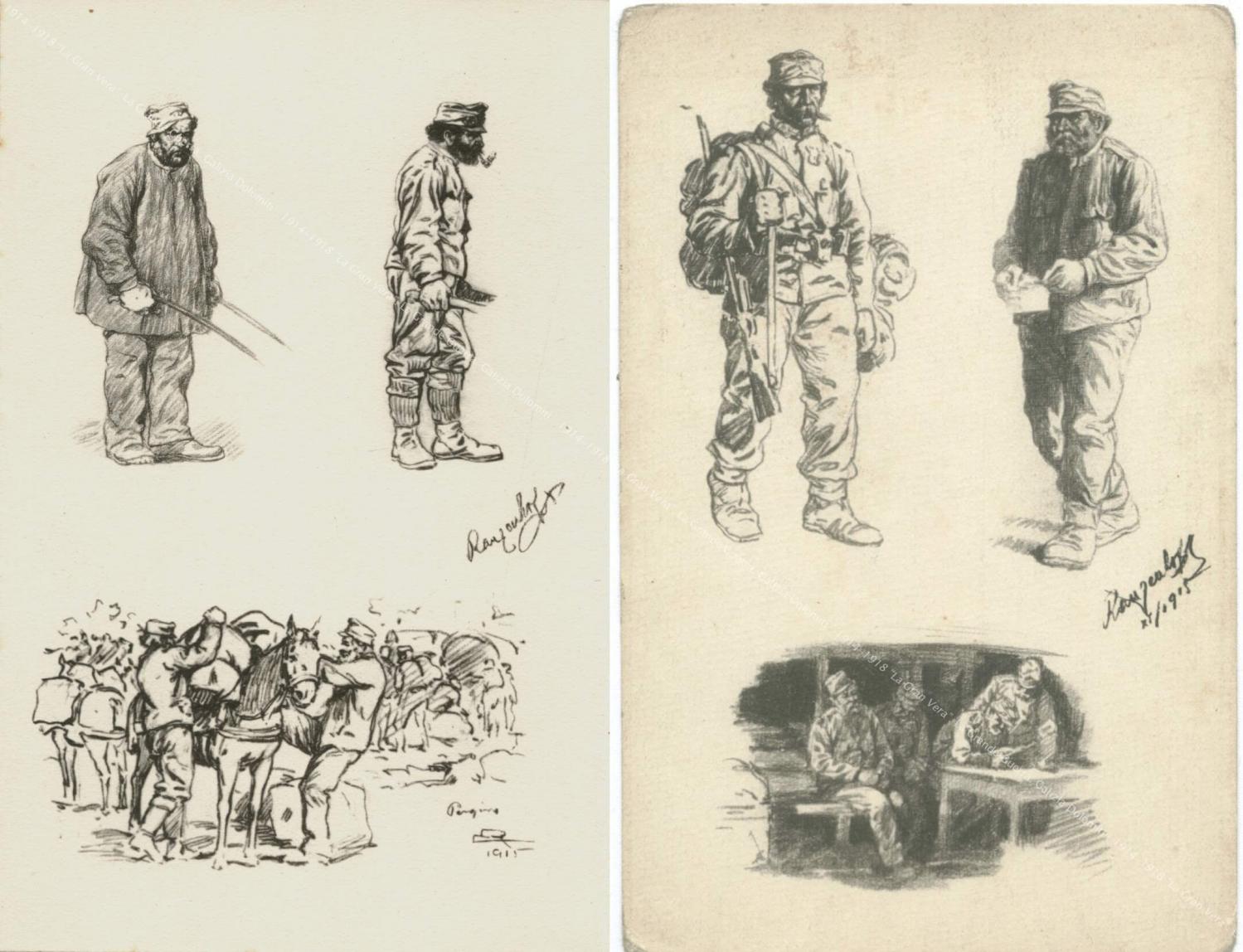

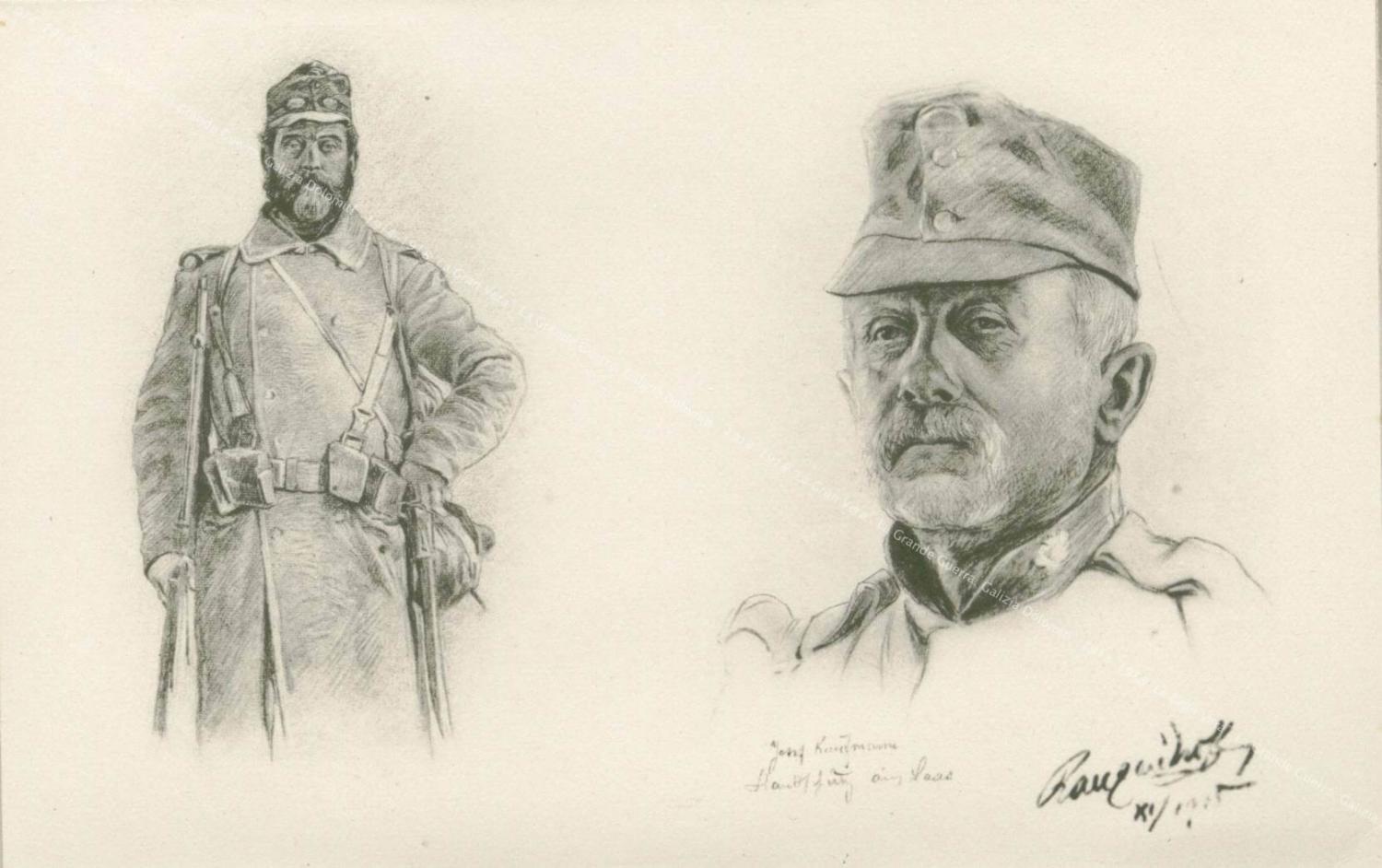

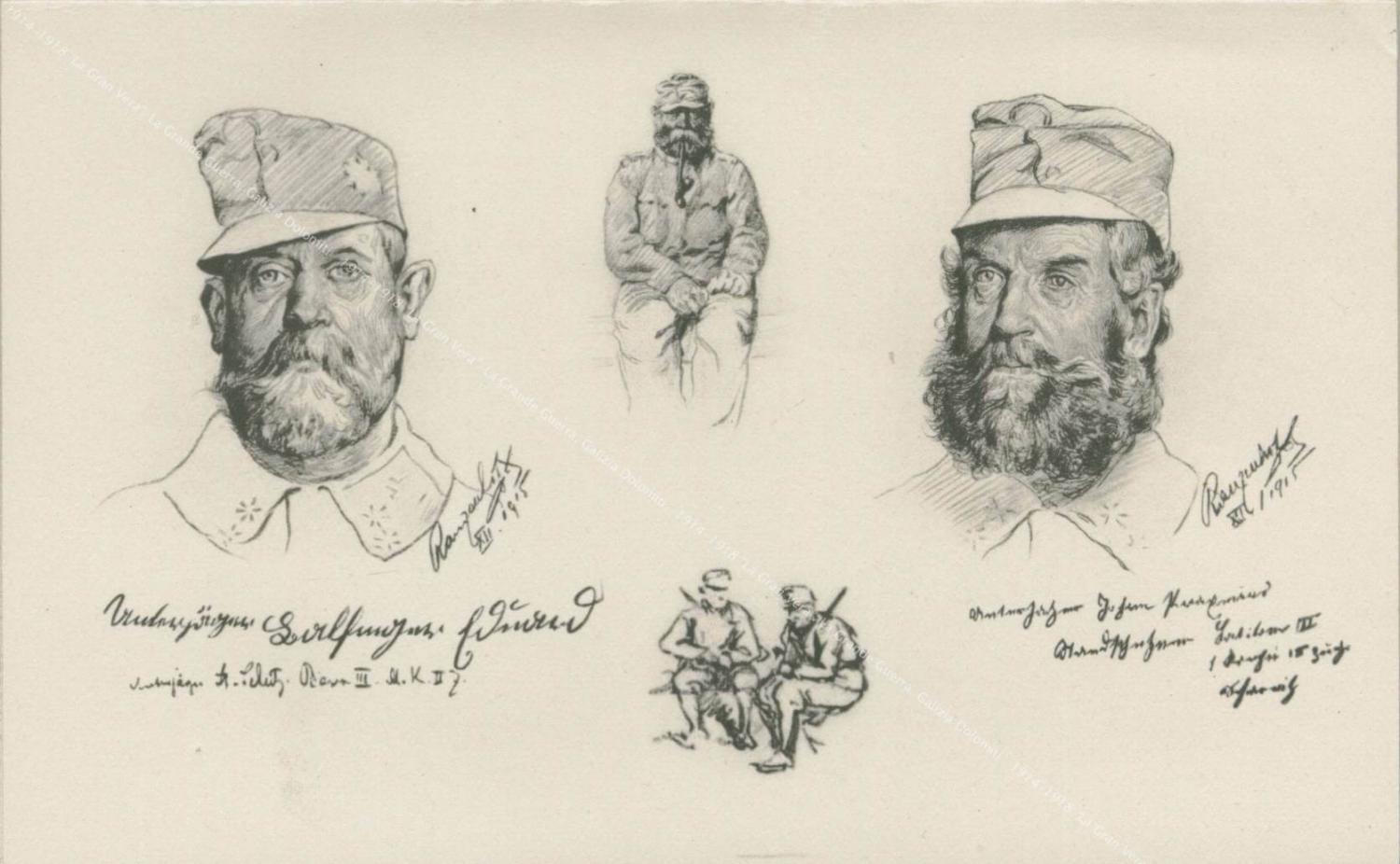

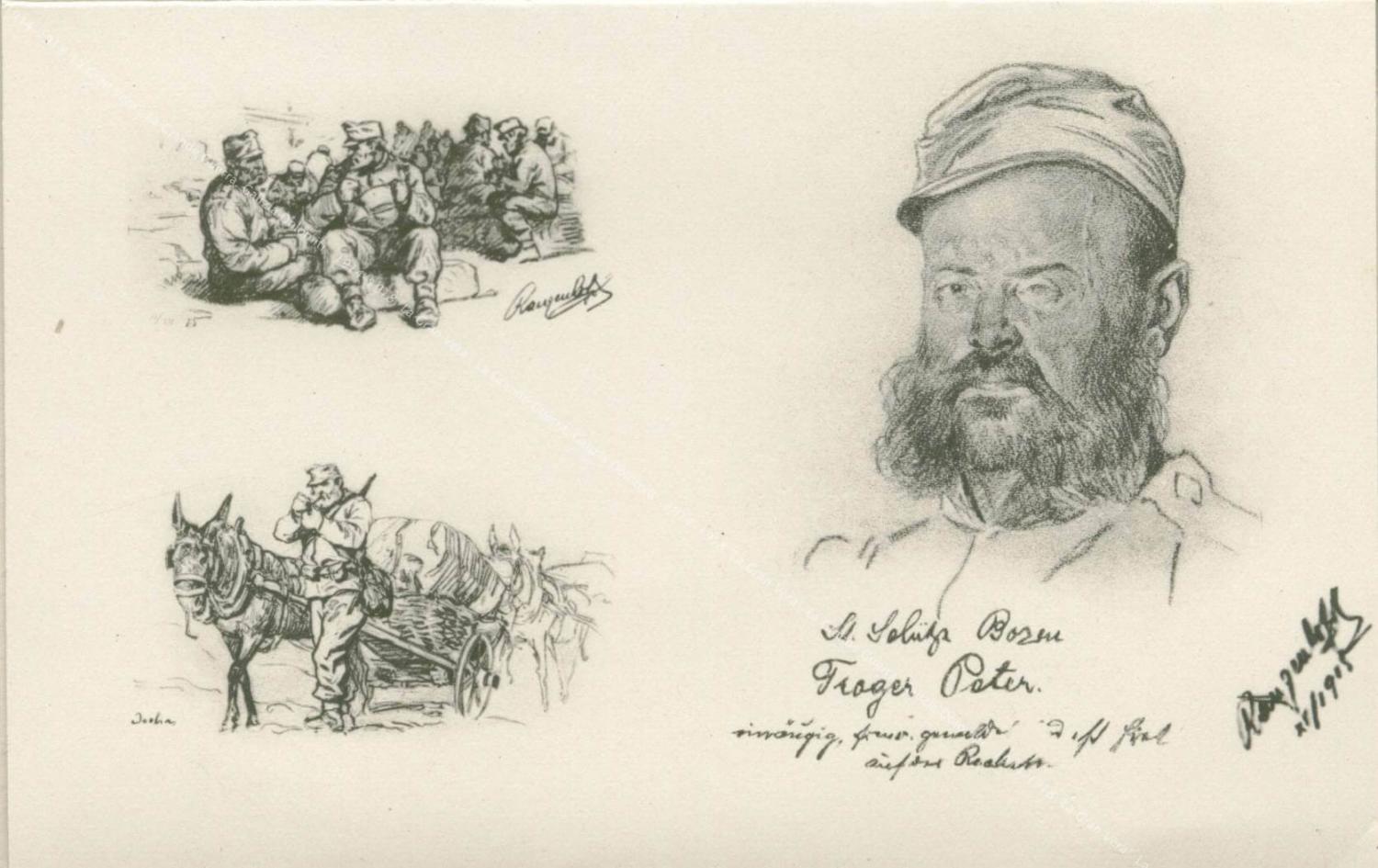

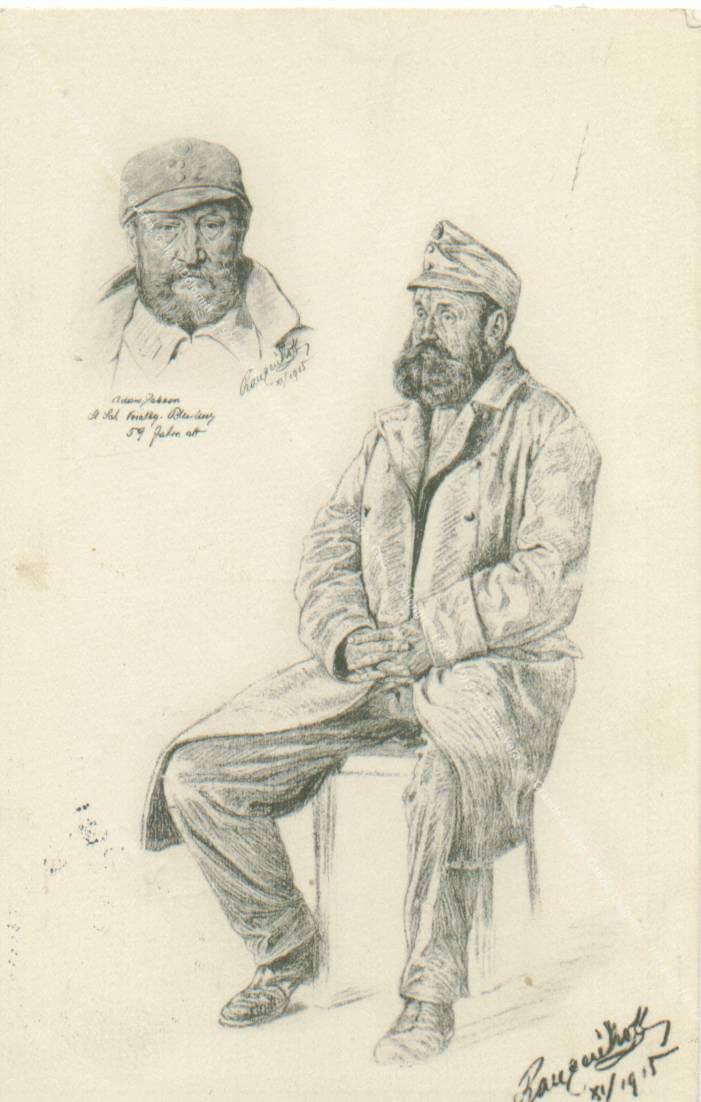

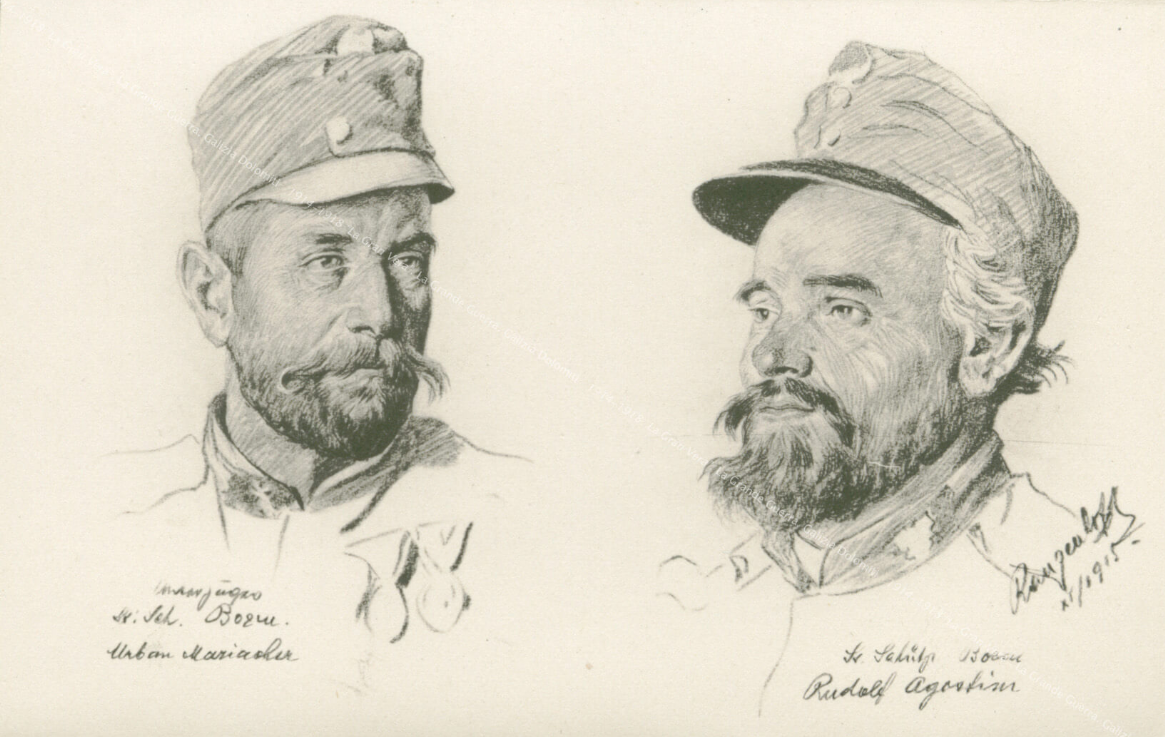

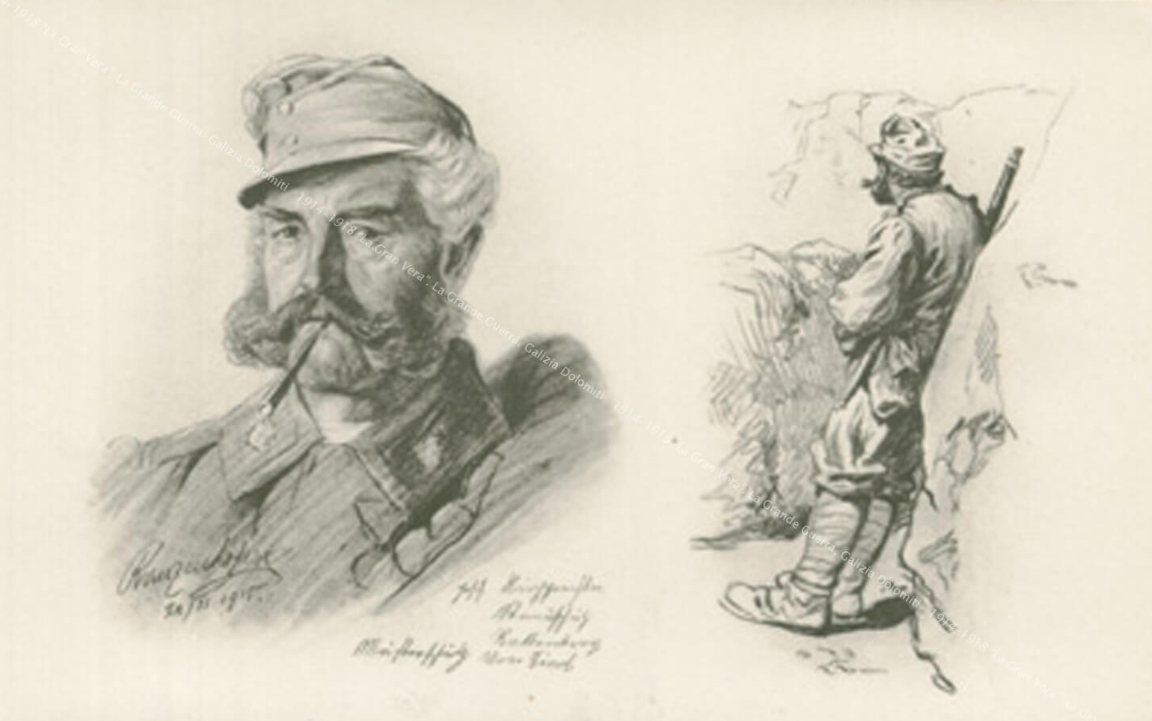

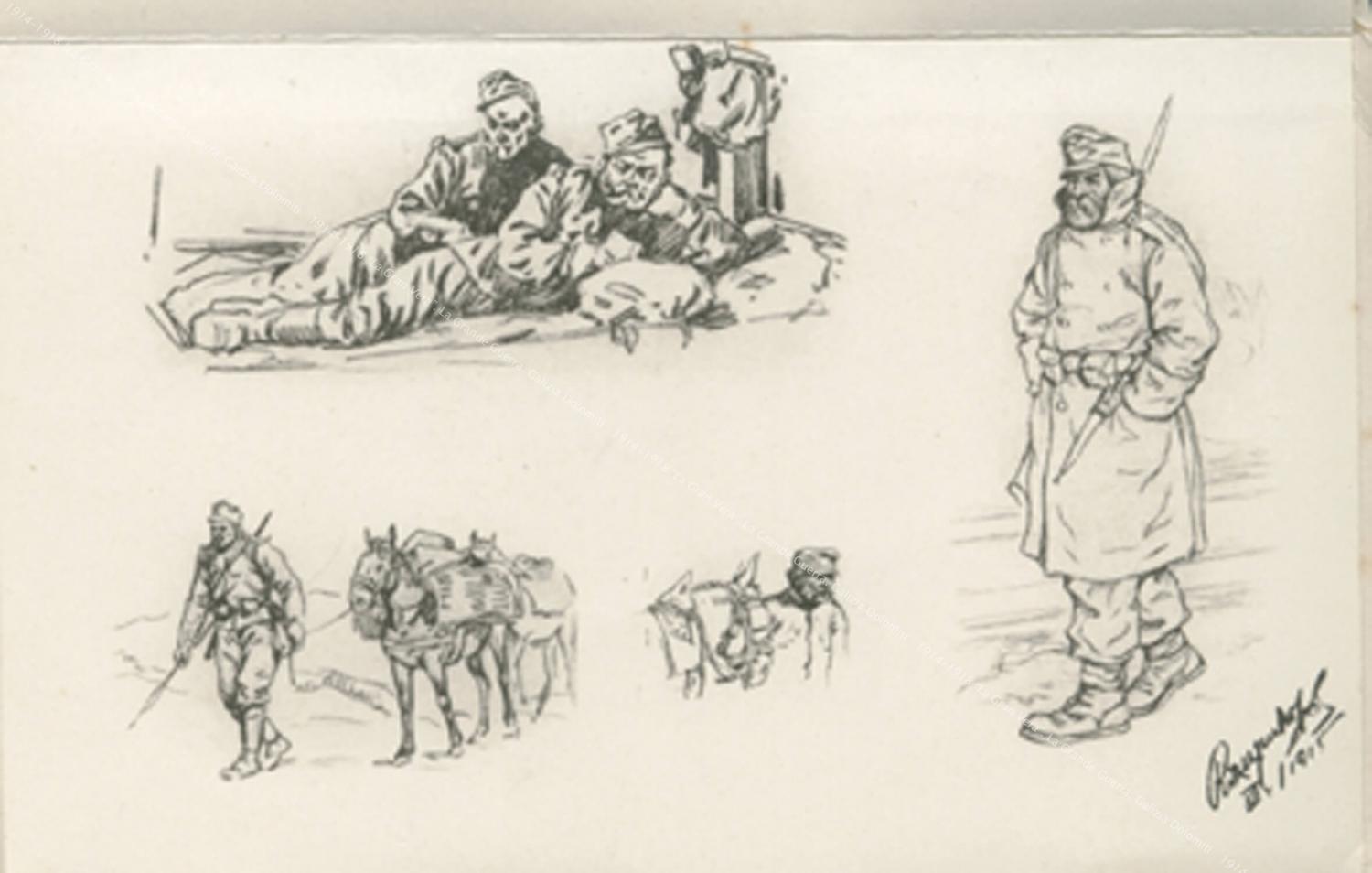

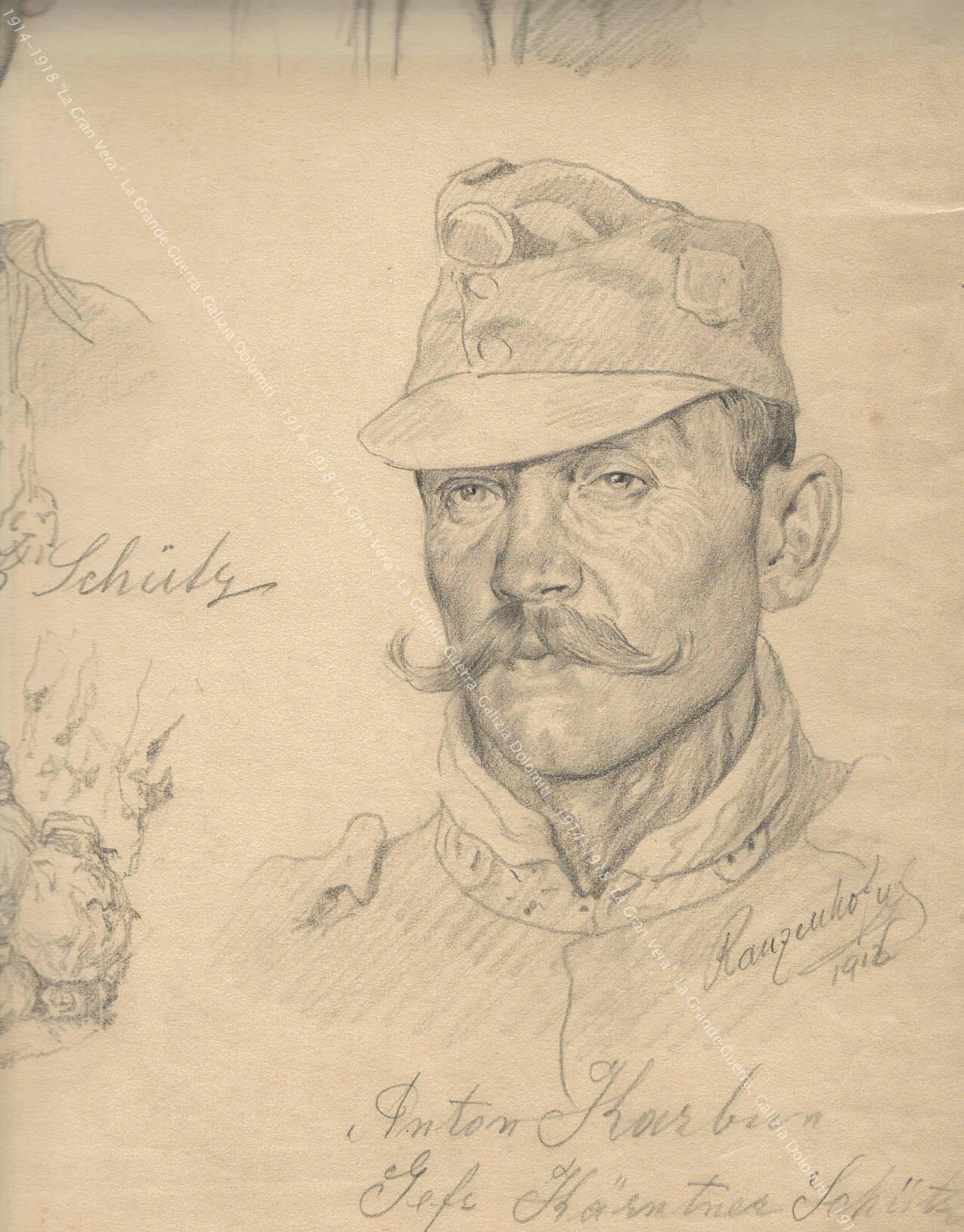

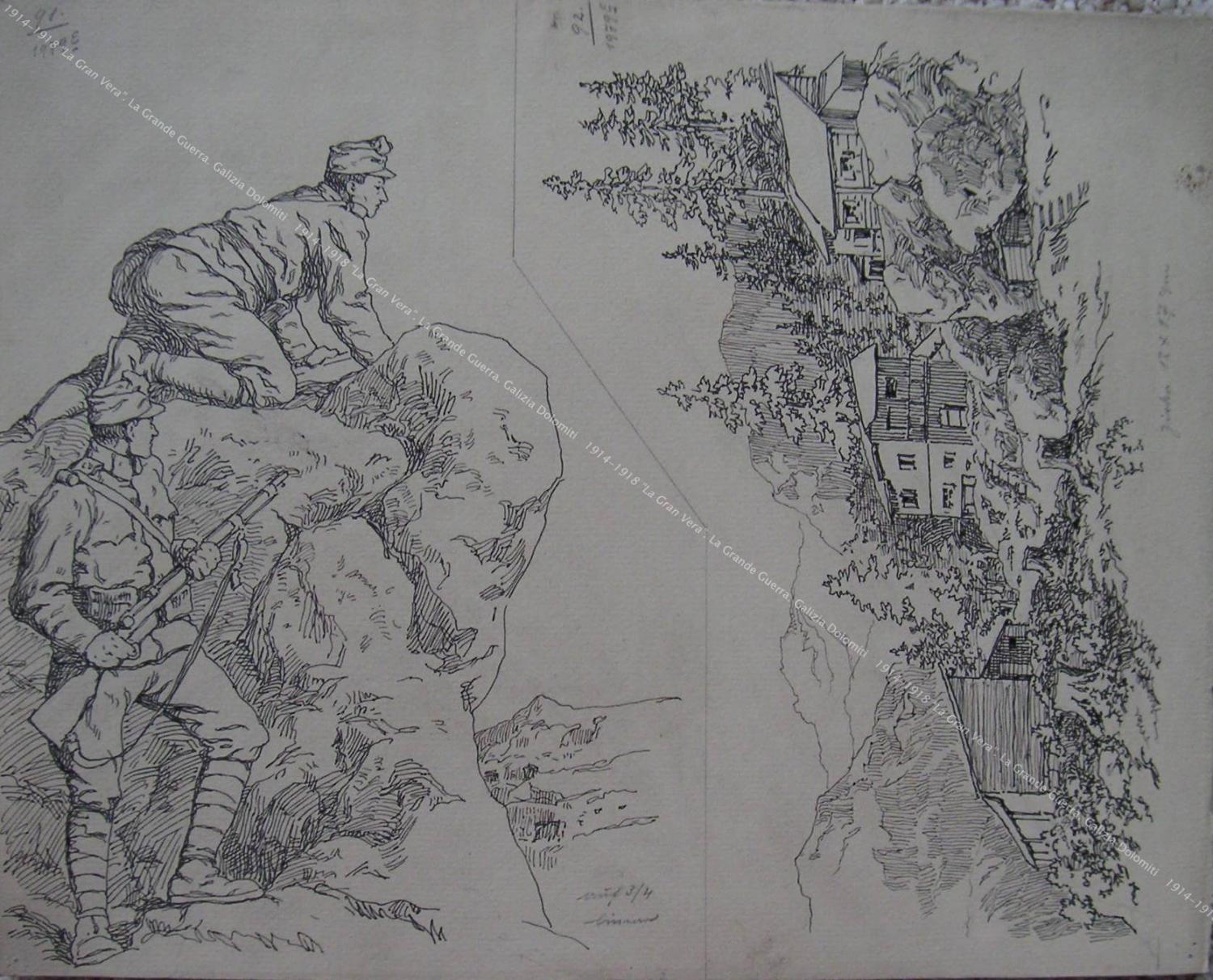

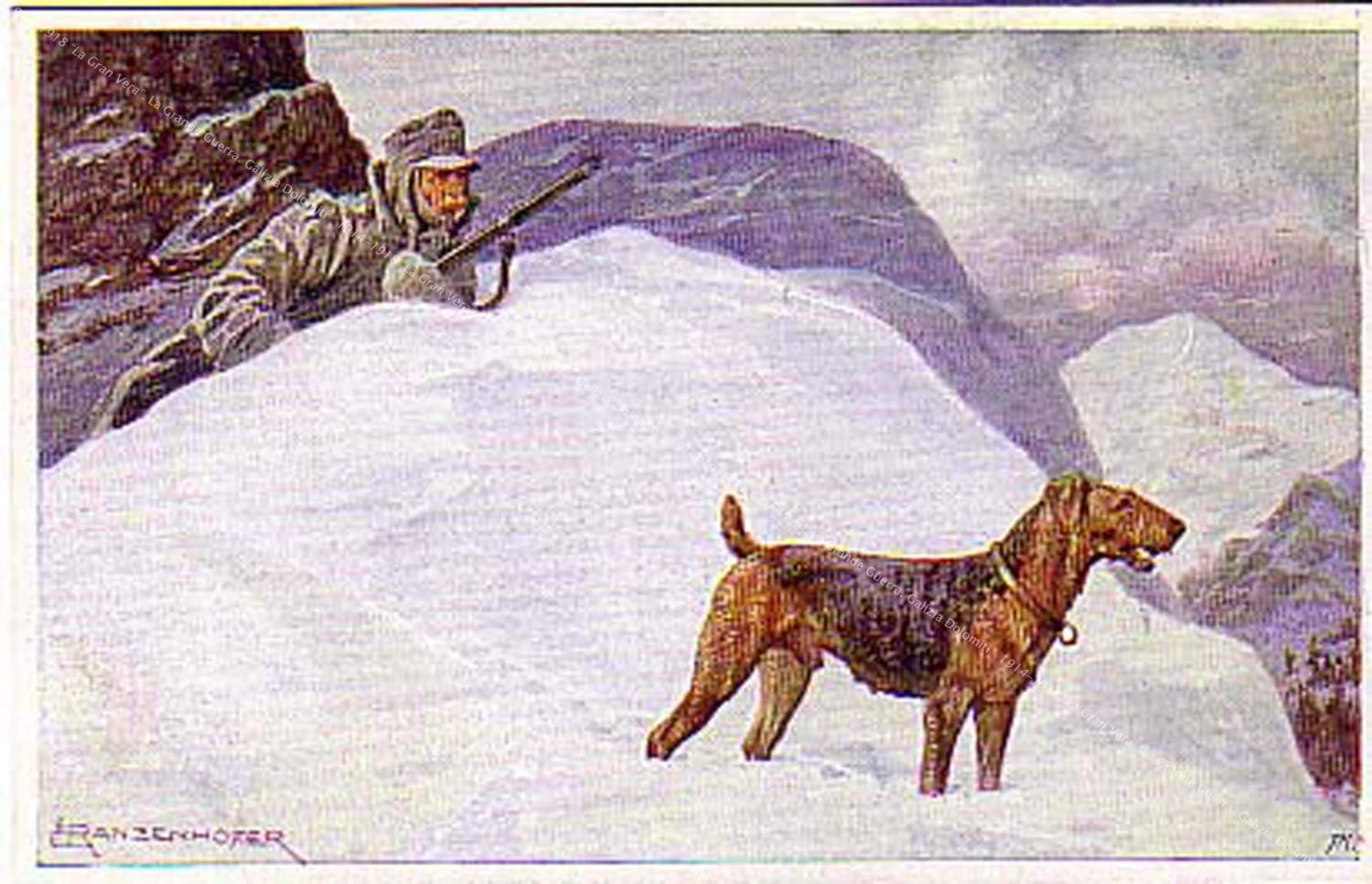

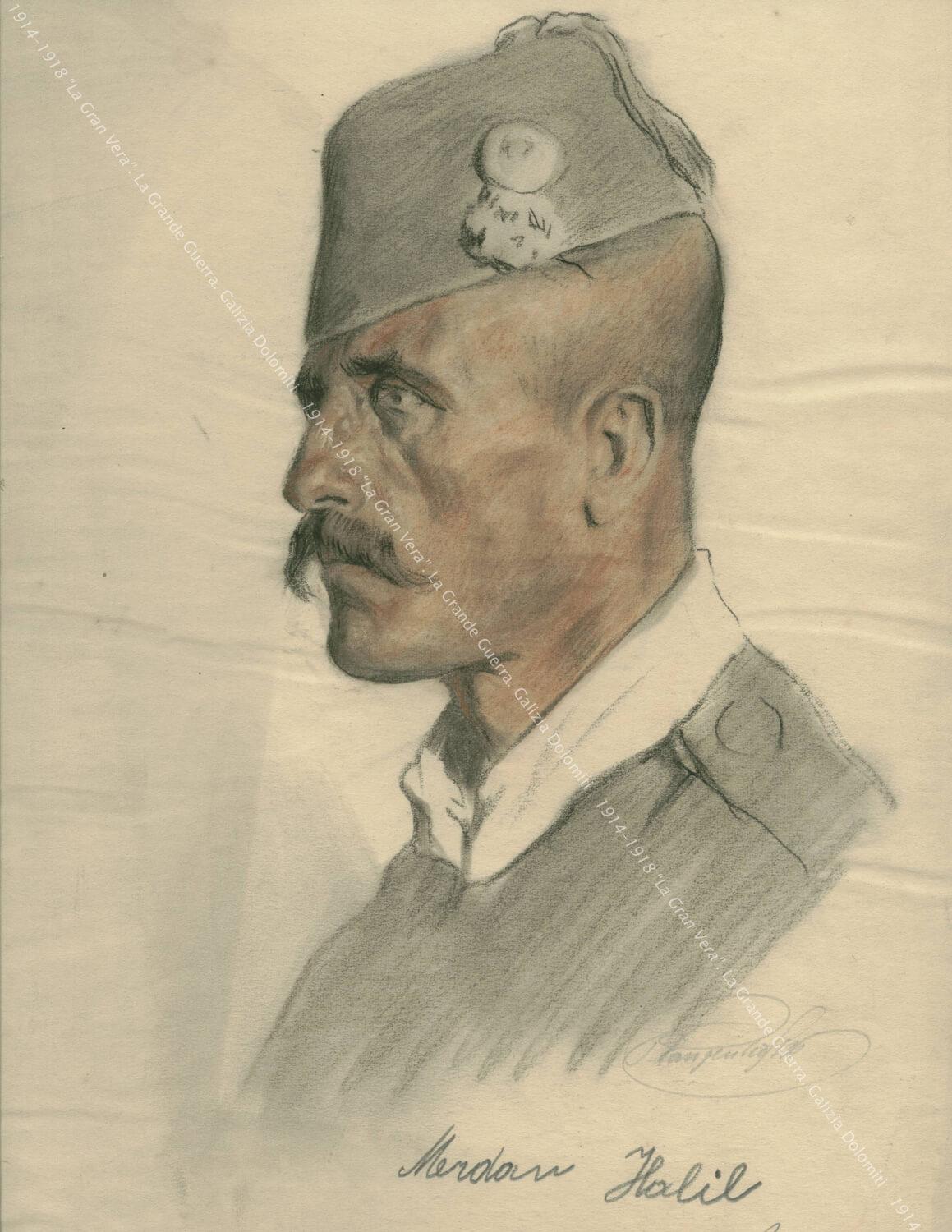

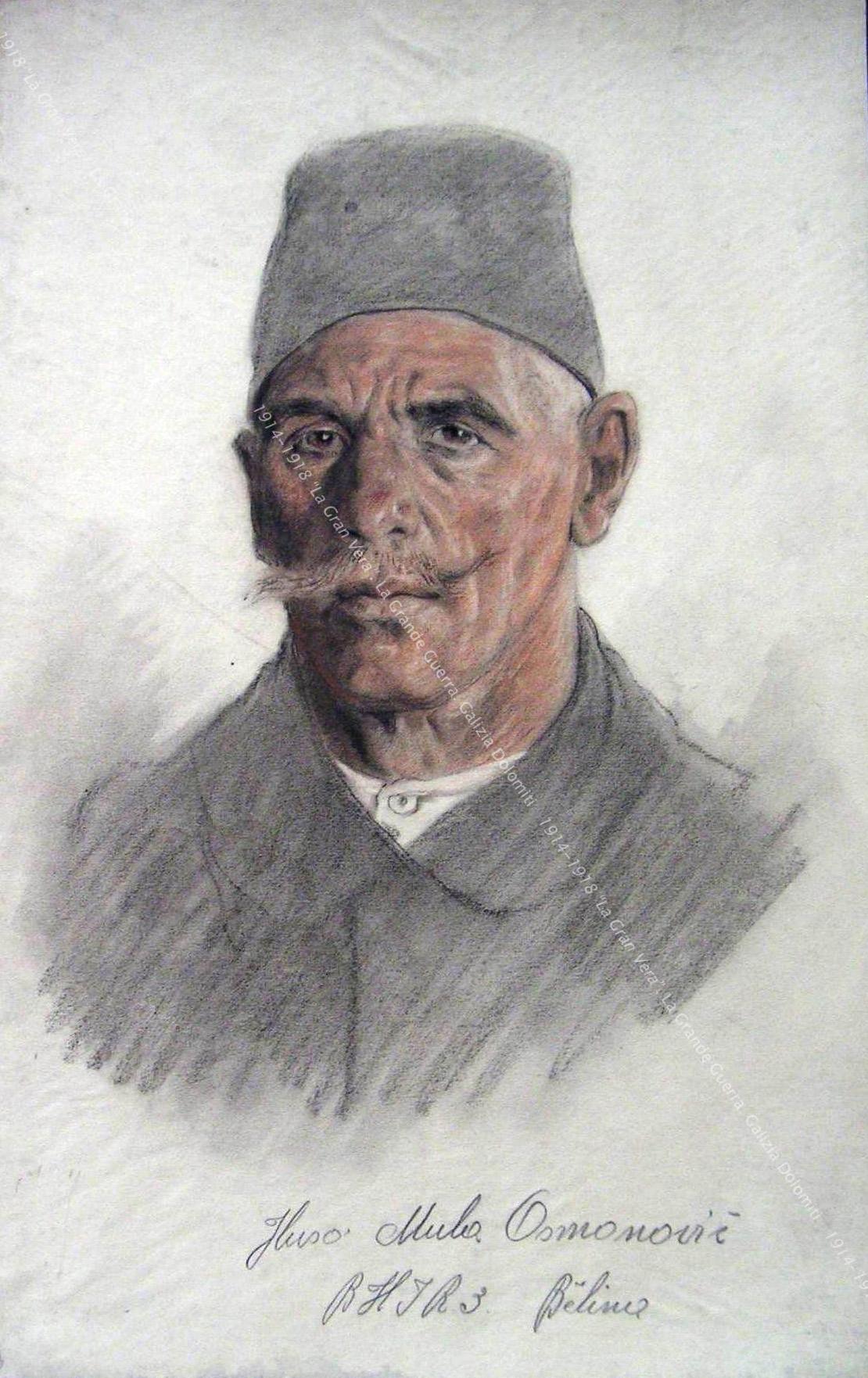

Emil Ranzenhofer was a prolific artist who worked in Vienna between the 19th and the 20th centuries. He designed ex-libris, posters, postcards, documents and certificates for the National Hebrew Union. He also worked as a war artist at the Press Office of the Supreme Command in Austria, which is why many of his works depict WWI scenes. Among his most remarkable works are those dedicated to the Standschützen, where he often painted individual portraits or Alpine war scenes, indicating the names of people and places.

This is how he wrote to his superiors: “Studying the characteristics of the Austrian peoples and in particular the Alpine ethnicities has always been an important part of my artistic efforts. With the insurgence of the patriotic wave, I wished to serve my Country by portraying the popular soul of the inhabitants of the Alpine region, in particular the Standschützen. In this matter, I believe I have created my most refined works.”

For this reason he made a Tyrol Almanac and a collection of Standschützen sketches and portraits, contacting the propaganda offices to obtain the necessary permits and support.

Thanks to Judith Kanner Gordy, to this day in charge of the memory of E. Ranzenhofer, we can display to the public, for the first time in Italy, a significant number of reproductions of sketches, drawings and watercolours he made during the war.

www.ranzenhofer.info

This work contains the essence of the war experience: combat, lookouts, strenuous transportation, meetings with Italian prisoners, but also pleasant breaks with smoking and playing. This colour plate also allows us to perceive the many colours of the uniforms cobbled together from old or unsold stock.

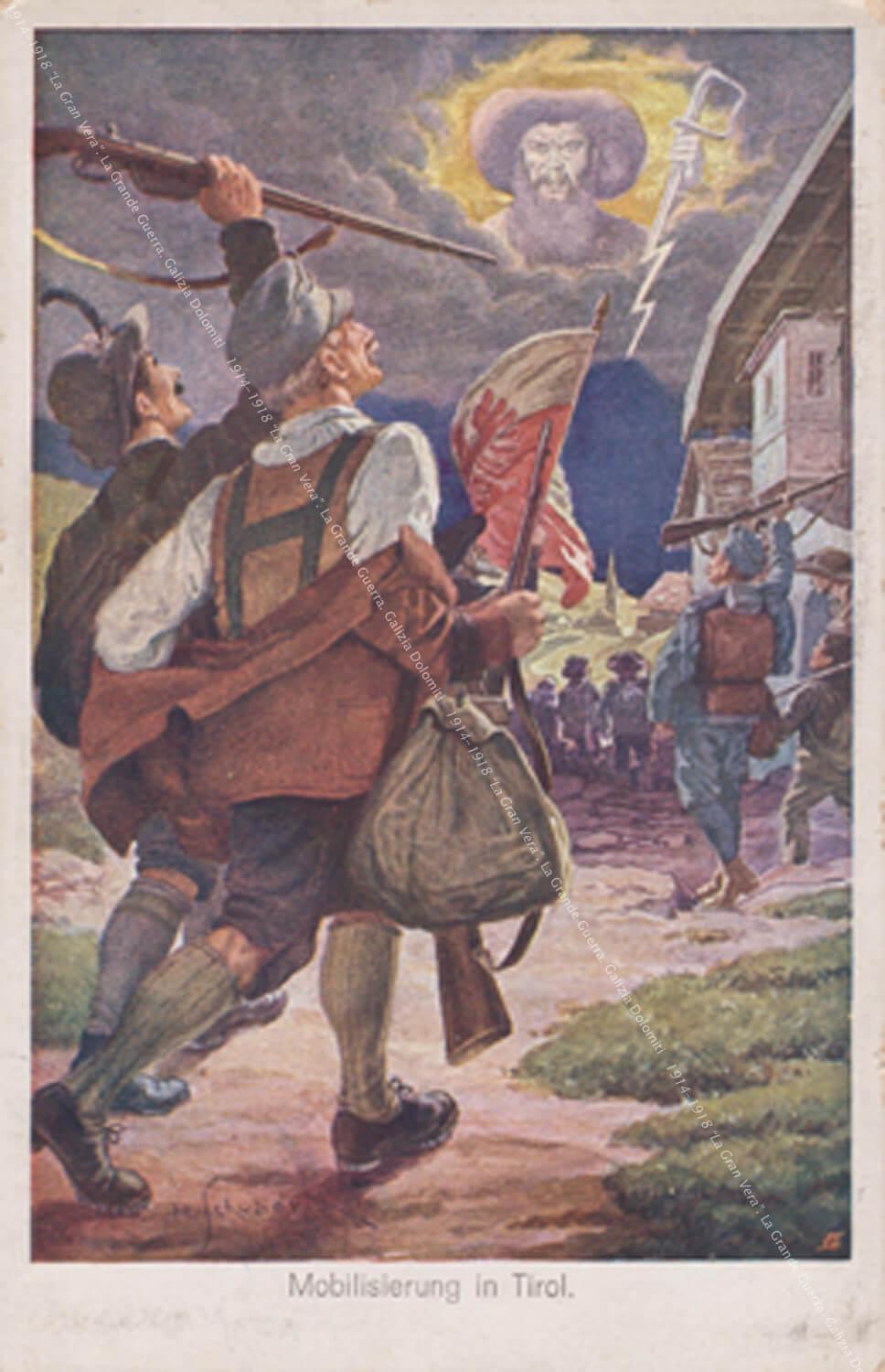

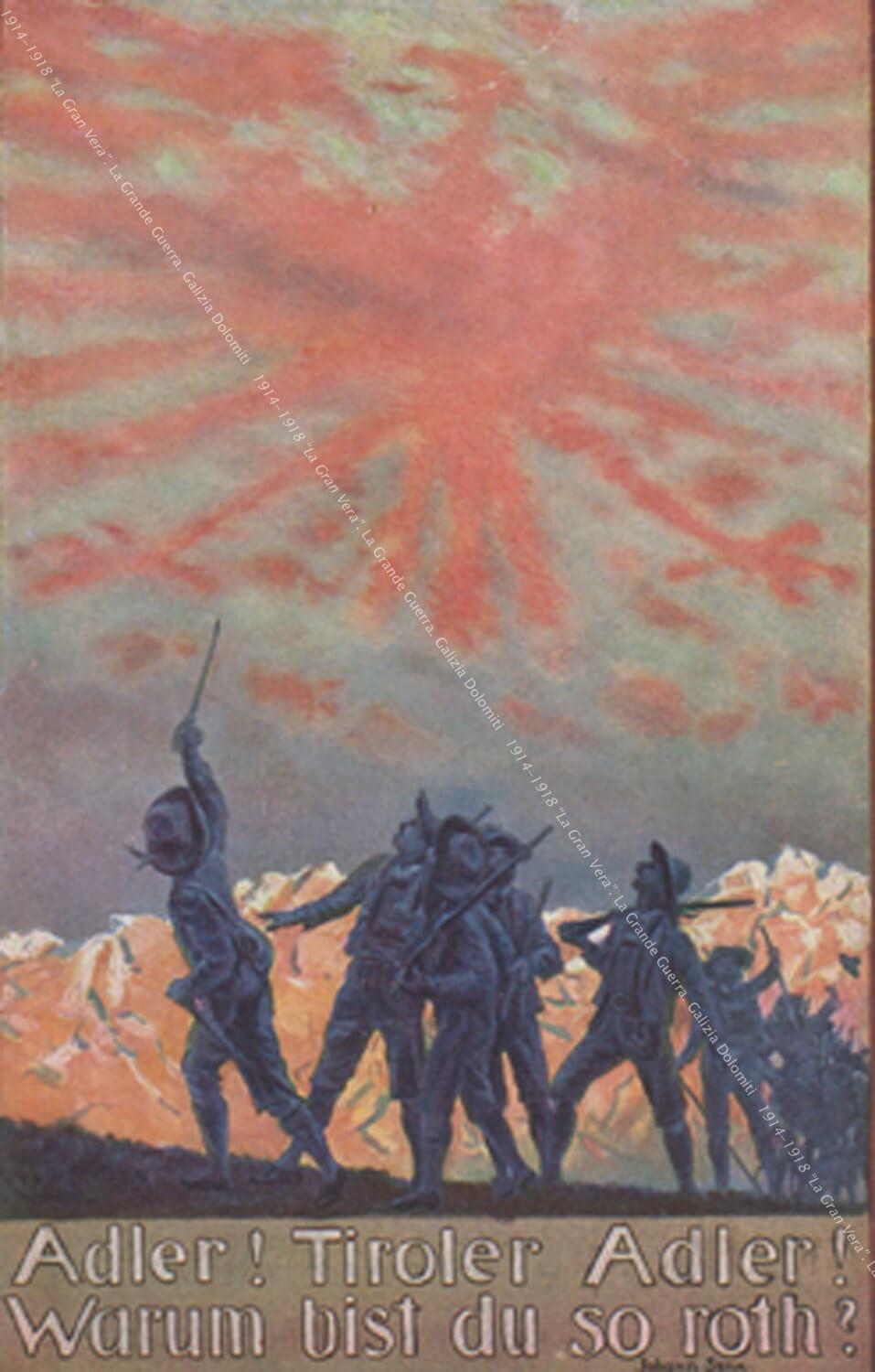

Emil Ranzenhofer drew a series of eighteen postcards as commissioned by the Press Office of the Ministry of War, sold to the public to finance assistance and provident agencies. They are a tangible sign of the extreme interest of propaganda in the loyal behaviour of Tyrol inhabitants. Emil Ranzenhofer began a long correspondence with the press office to carry out this important work.

All images measure 9 x 14 cm and were published in sepia and in black and white, while the back shows these words:

Offizielle Karte für: Rotes Kreuz, Kriegsfürsorgeamt - Kriegshilfsbüro

K.F.A. Tiroler – Standschützen

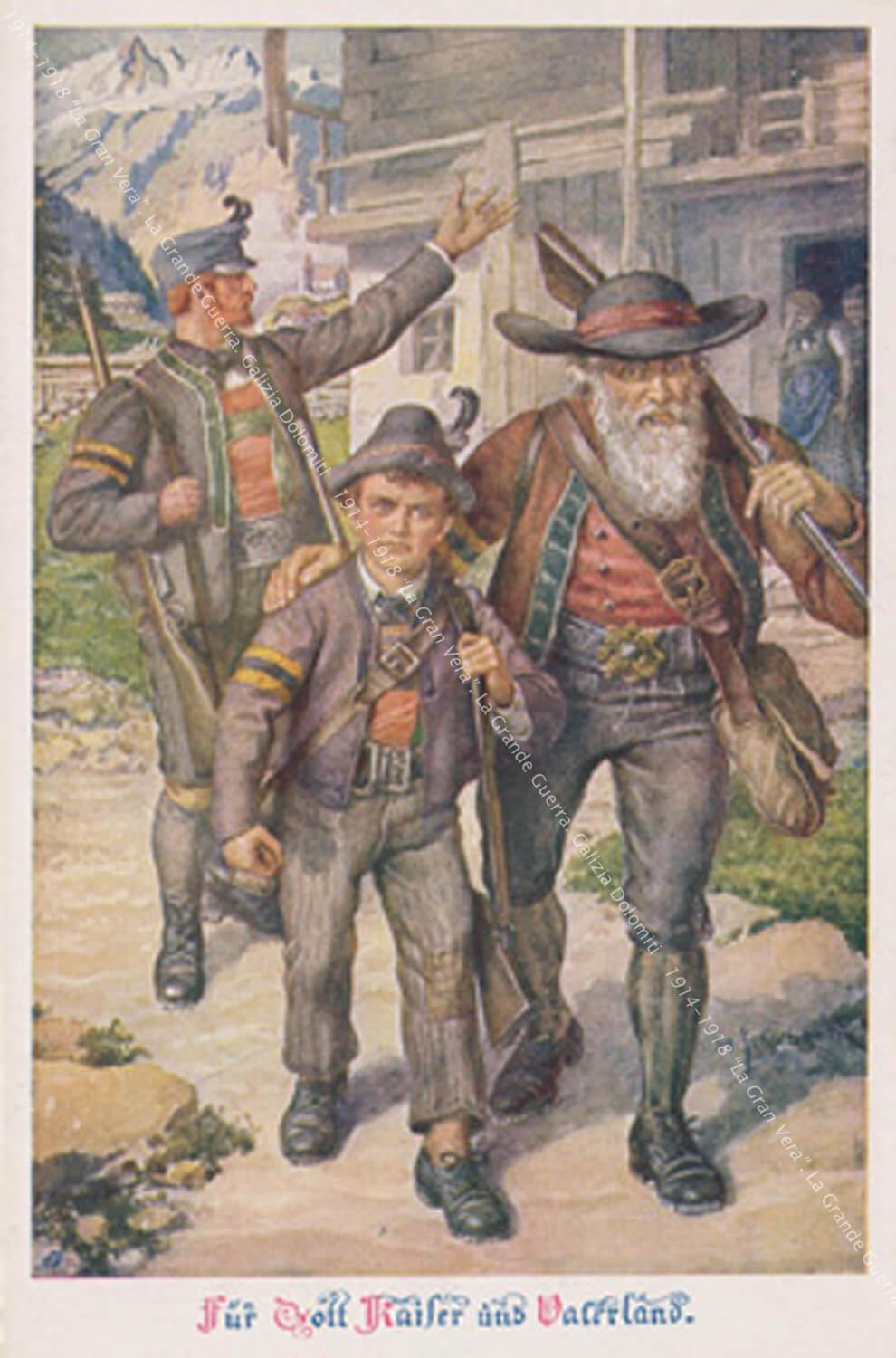

These two works by Ranzenhofer are characteristic of the propaganda at that time and are quite different from each other, connecting the collective imaginary of the Tyrol costume and the figure of national hero Andreas Hofer. Many works portray young and old soldiers departing for the front, abandoning their farms for love of their country. It is partly true that Tyrol inhabitants reached the first line without issued uniforms, wearing the yellow and black band around their arm used to turn civilian clothes into military attire - the uniforms were only distributed a few weeks after the war had started - but it is also true that they did not depart in their traditional clothes. Propaganda intended to use these works to connect the renewed defence of the Country to Napoleonic wars.

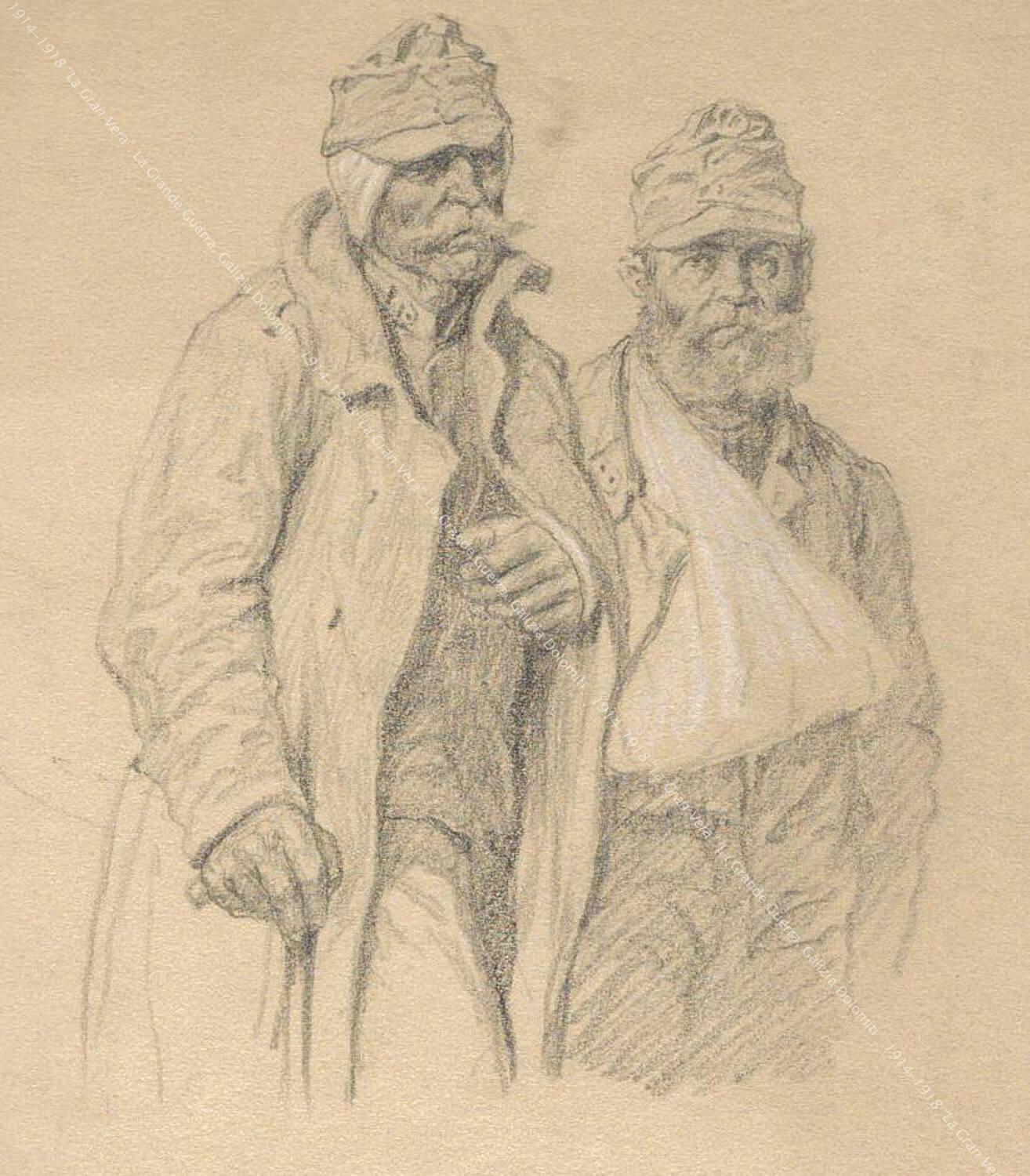

Another way of portraying reality, very similar to that of Emil Ranzenhofer, was used by his colleague Albin Egger-Lienz (1868-1912), who painted numerous scenes during WWI and from whom we pick this strong image as a sample: “The oldest and the youngest”. This painting shows two Standschützen early in the war, still wearing the uniforms used at the beginning of the conflict, characterised by the “pike-grey” colour and previously destined to the Kaiserjäger.

The oldest is leaning on the obsolete Stayer Mannlicher M.1888, while the youngest is carrying a Stayer Mannlicher M.1895 carbine.

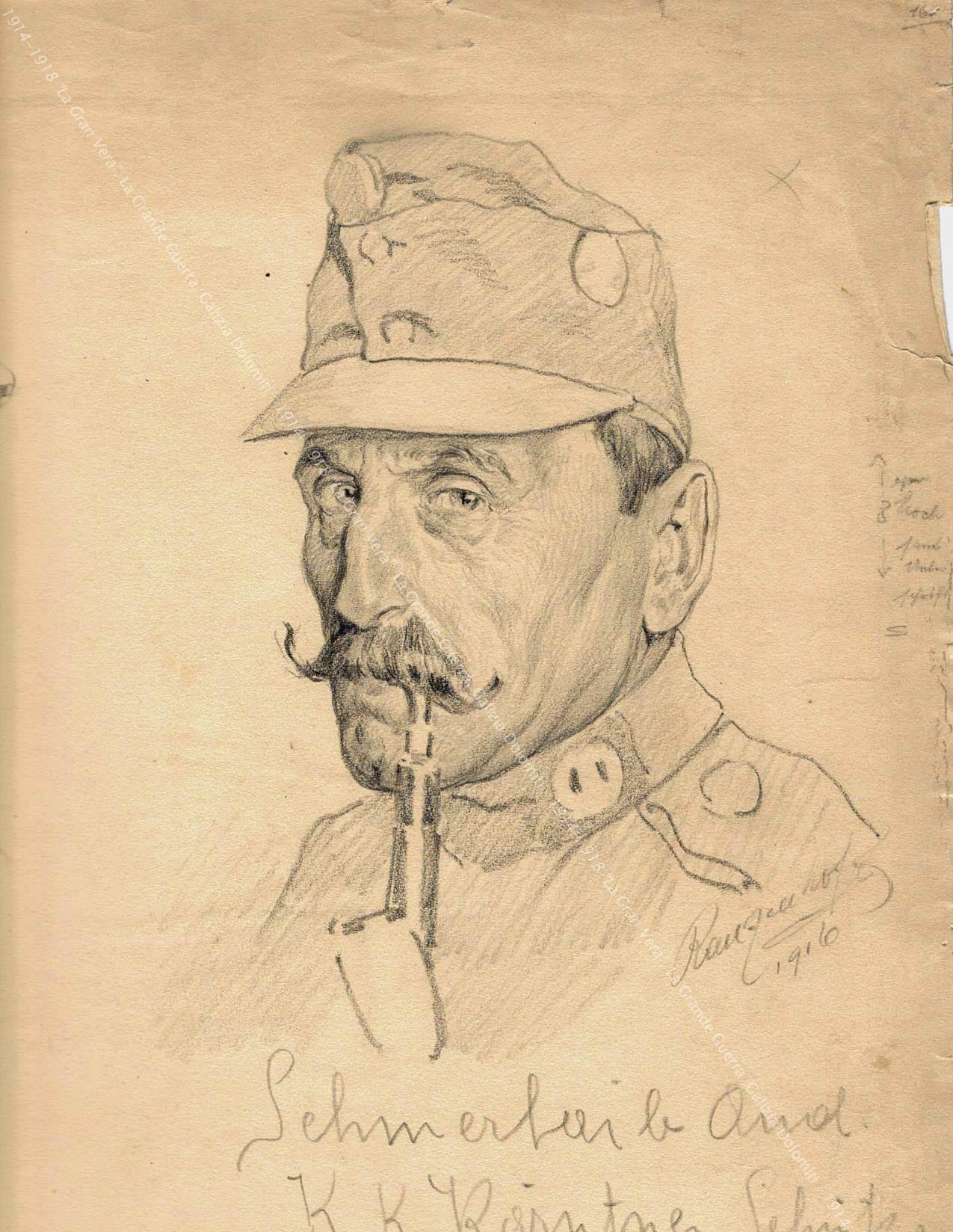

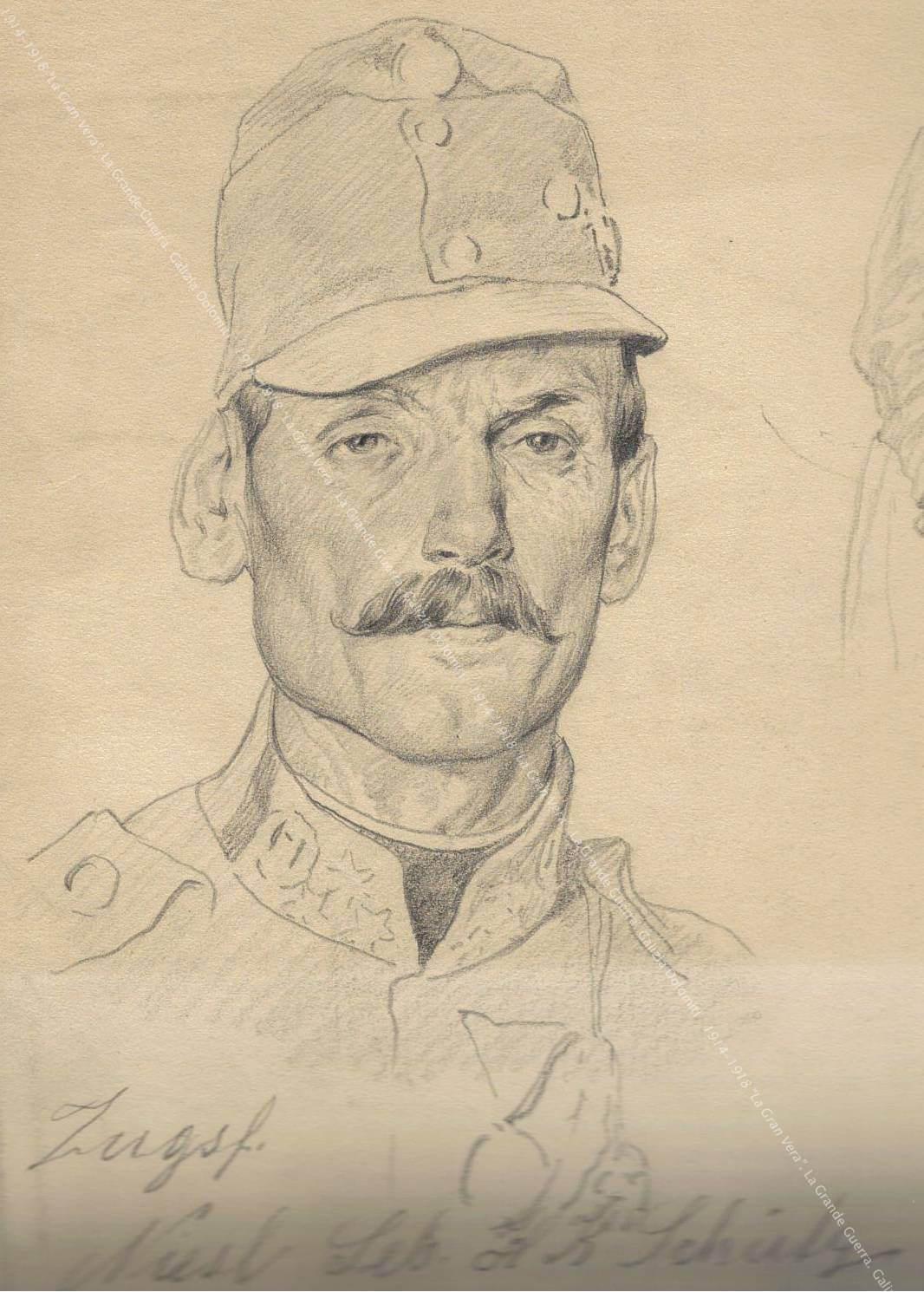

Some portraits display the typical expressions and, perhaps, the face features of the mythical figure of Hofer, and as a consequence were adopted as models by the Standschütze.

Long beards were a typical ethnic feature of that time: they were allowed or “pardoned” for the Schützen because they were actually part of national tradition, although they were not usually admitted in the army.

Scruffy helmets, a ratty air and yet a proud look in their eyes are some of the characteristics that Ranzenhofer gathered and managed to communicate. Proud old soldiers, whose names and corps are informed.

The ethnic types seem like faraway things when seen with today’s eyes, but one hundred years are not many, and by then national pride was a very strong characteristic, unfortunately strong enough sometimes to drive populations into disastrous wars. Even pipes are an element of ethnic distinction and acknowledgement.

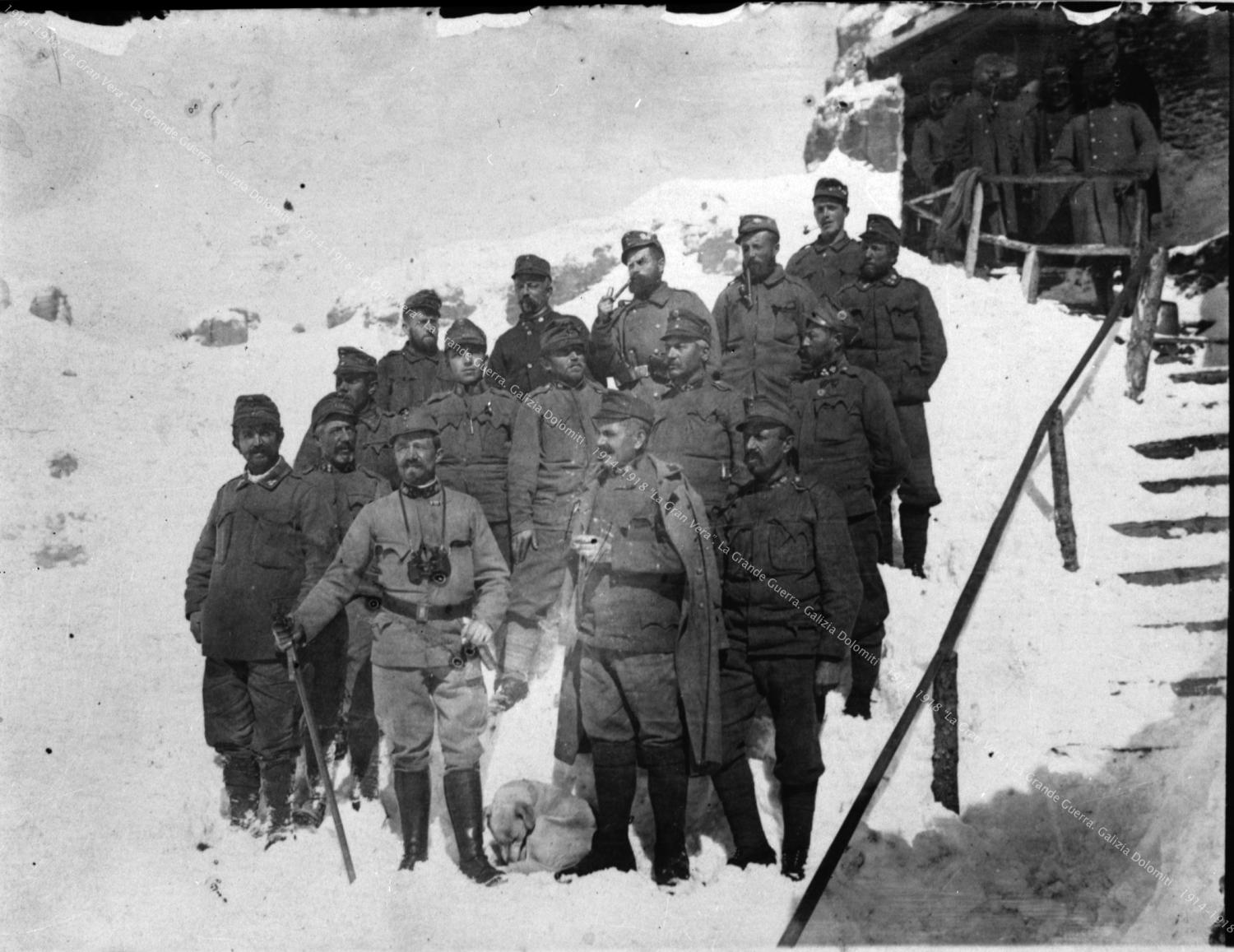

The Standschützen of Val Passiria posing proudly with Commander-in-Chief Josef Freiherr Roth von Limanowa-Lapanów, (1859-1927). The image shows the value attributed to their role. They are the men and the expressions that Ranzenhofer portrays with refined skill.

Faces tired of the war and of the years. Many of these peasants had already been in the military during peaceful years, and their unexpected return to the front meant leaving their farms, their planting, their livestock behind, under the care of women. This led to strong concerns and anxiety in a self-sustaining economy. Permits were sometimes given for harvesting or for the picking of the fruits of the land.

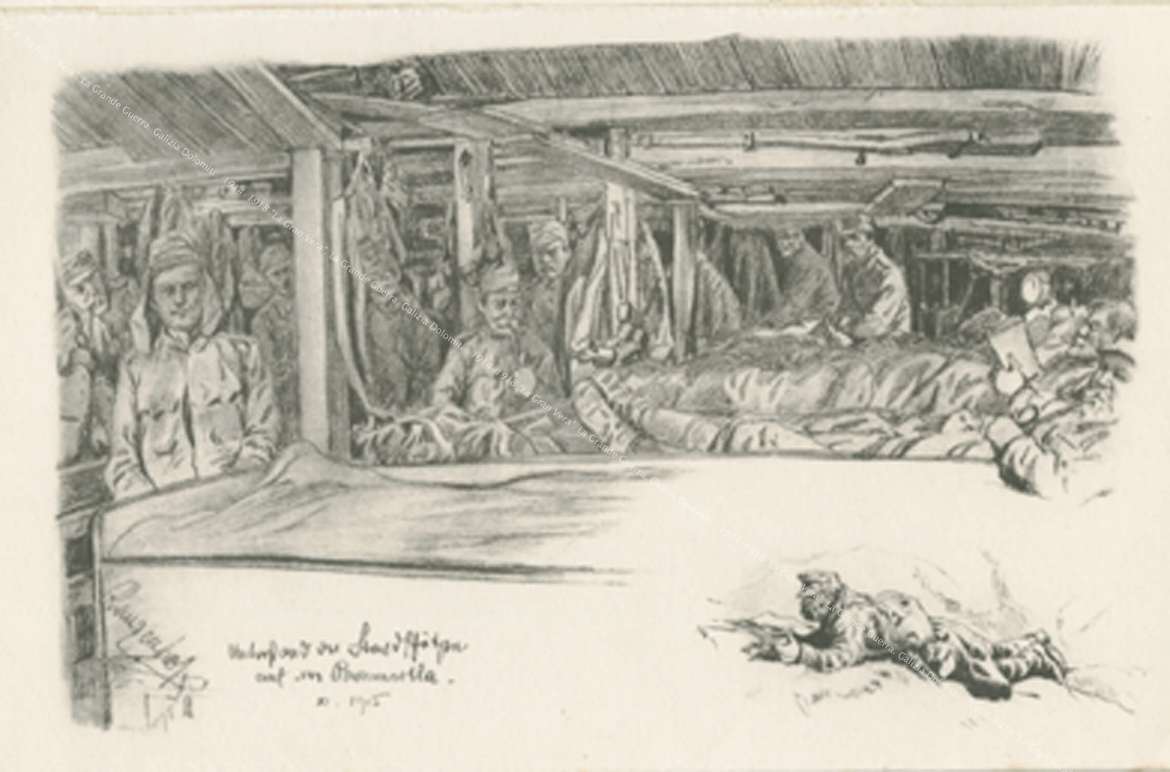

An extraordinary series of sketches that catapult us into the everyday life of war in Tyrol:

transport, resting soldiers, guarding shifts, animals and men.

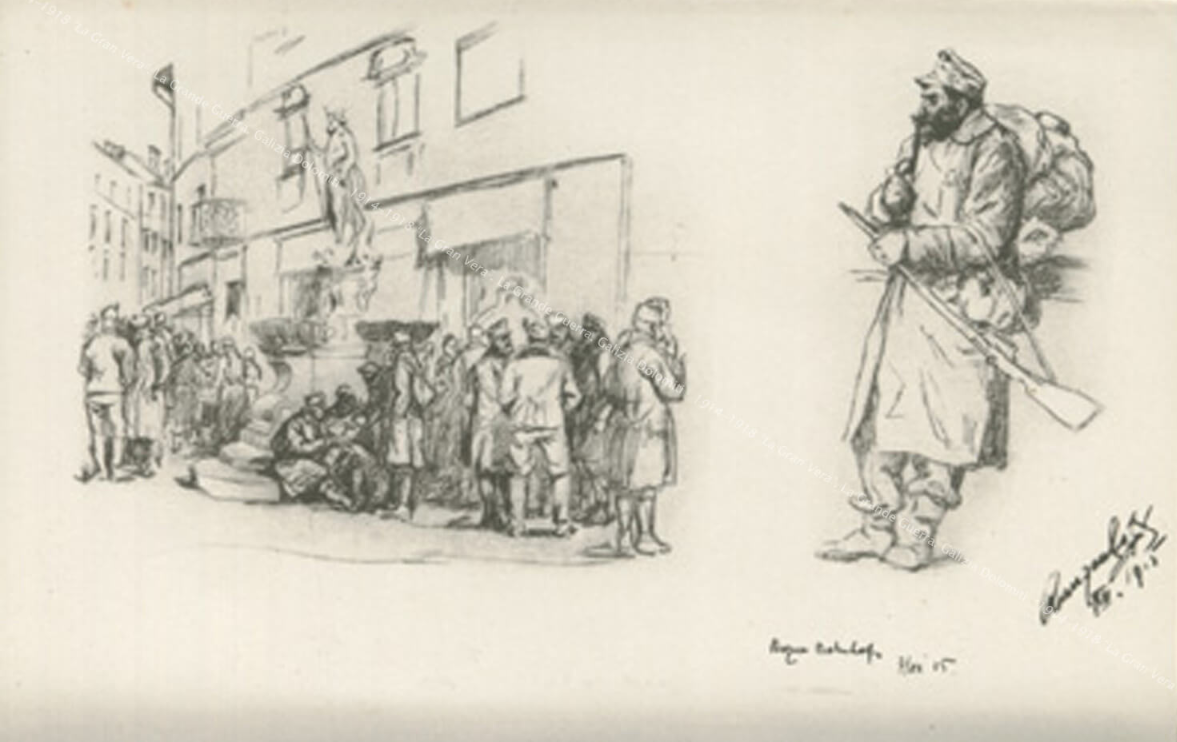

An extraordinary image of Austrian soldiers gathered around the fountain in Piazza delle Erbe, in Bolzano.

The back of a cavalry soldier wearing a short fur-lined jacket (Pelzrock). Standschützen and Kaiserjäger in calm conversation while only a few kilometres away, on the heights of the Fassa Valley, death harvested its plentiful fruits.

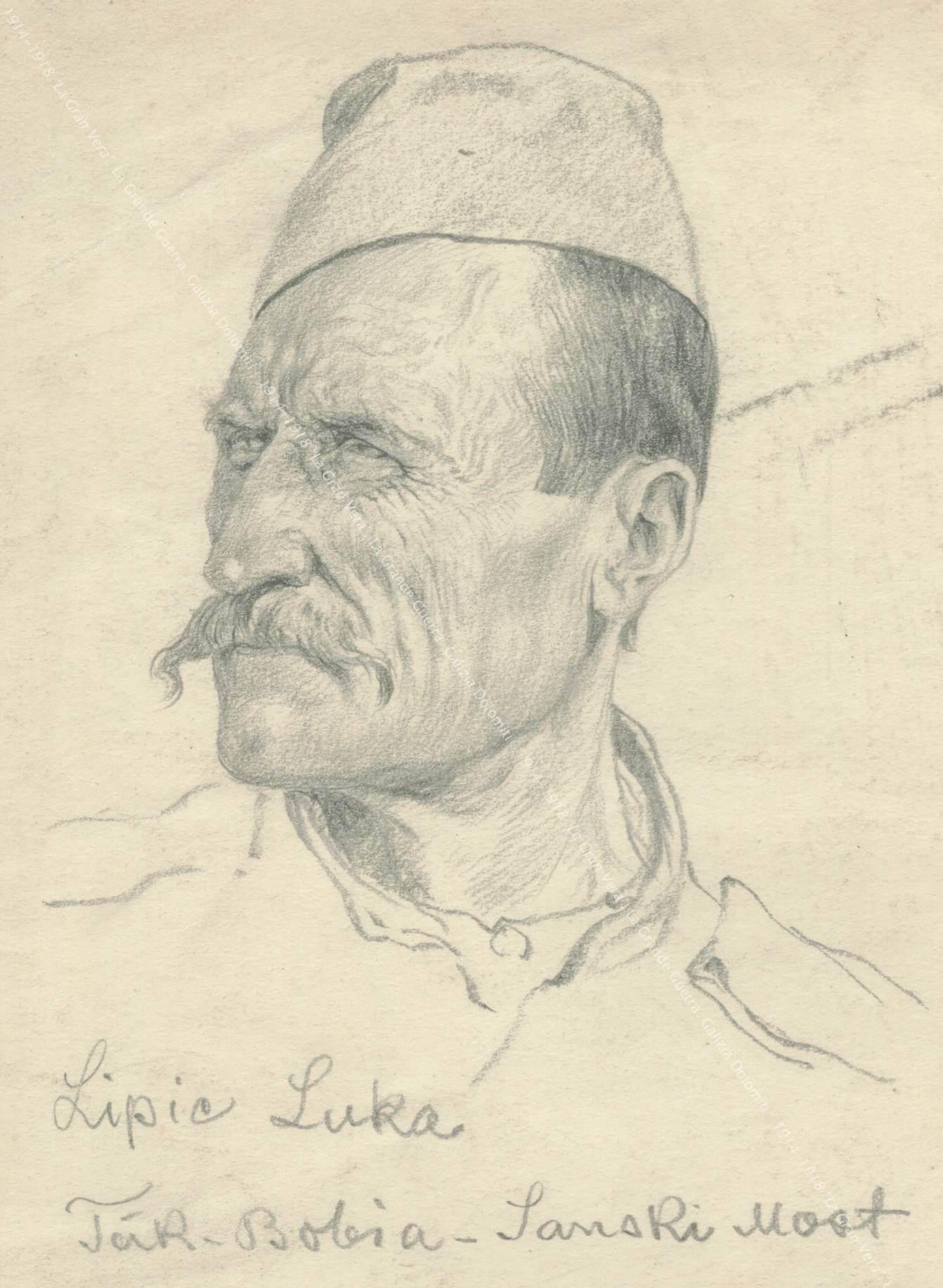

As examples of Razenhofer’s ability to portray human souls, these four Standschützen portraits are meaningful for their intense expressiveness. Ranzenhofer surely got into contact with his models, wrote their names and their troops of origin, the date on which the work was made and often the place as well. They are faces of old soldiers, under the strain of fatigue, hunger and the war, soldiers whose eyes tell us about the suffering of the battle.

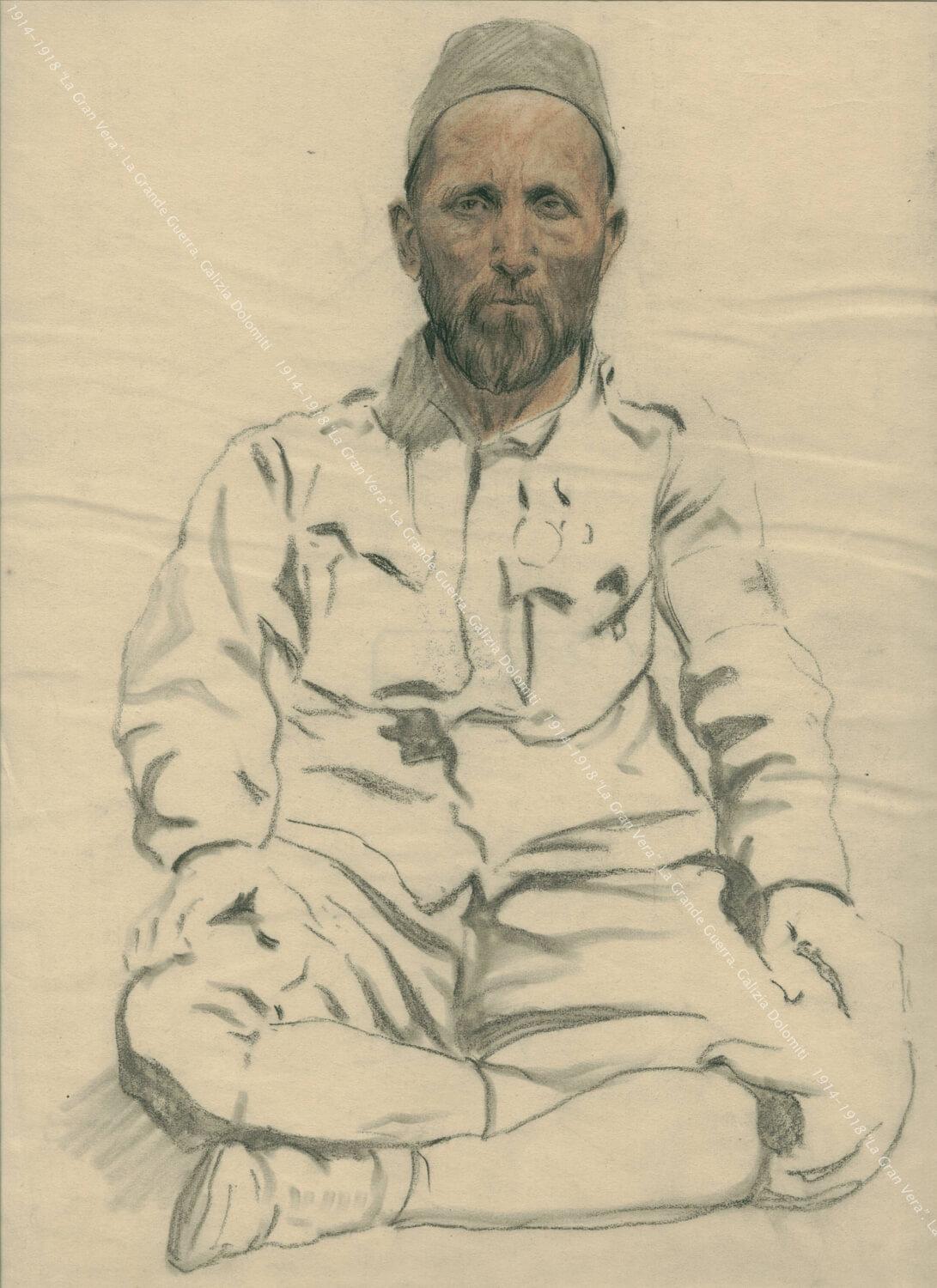

For a certain period, E. Ranzenhofer came into contact with Bosnian soldiers.

Their essential particularity was the fact that they were Muslims, which gave them some autonomy: different food, wearing a fez (Tarbusch) and the presence of an imam instead of a chaplain. The Bosnians were excellent soldiers, to the point that the 2nd regiment was the most decorated Austrian-Hungarian regiment in the war.

In Moena, in particular in Cima Bocche, next to the soldiers of the 74th and the 92nd Infantry Regiments, to the III Landesschützen, the 37th Landsturm and the Standschützen of Moena, were the soldiers of the 1st Infantry Regiment of Bosnia Herzegovina.

These faces and these uniforms, with their typical fez, illustrate another little known part of the history of a complicated multi-ethnic empire.

Habits and traditions that surprised the inhabitants of the Fassa Valley with their diversity and that left strong traces in collective memory.

The Bosnians’ documented loyalty to the Empire was systematically cancelled out by the victors after the war, just like it happened to that of South Tyrol inhabitants who spoke Ladin or Italian.

Muslims and yet fiercely loyal to the Catholic Emperor Franz Joseph I, the Bosnians were courageous and ferocious fighters during the war. They fought for the honour of their battalion and their regiment first, considered equal to their own towns or communities, and, as a consequence, for the Empire.

Thanks to testimonies, we know that in Cima Bocche they would drink “chai” tea all the time, and only fought if absolutely drunk, although their religion forbid them from drinking alcohol. These “wild” soldiers returned from assaults to enemy trenches with parts of ears sliced from poor Italian soldiers displayed as trophies, shocking German- or Ladin-speaking officers who fought side by side with them in the high-altitude stations.

During the dramatic Italian attack to the Observatory of Cima Bocche in July 1916, the Bosnians scattered upon the arrival of the first Italian soldiers, but went back to battle when threatened by their own armed officers.

A rare event involving troops known for dying in position rather than losing their honour.